THE CITY WALLS OF SEGESTA – RECENT RESEARCH AND DISCOVERIES

Report from the 2025 campaign

News vom 13.05.2025

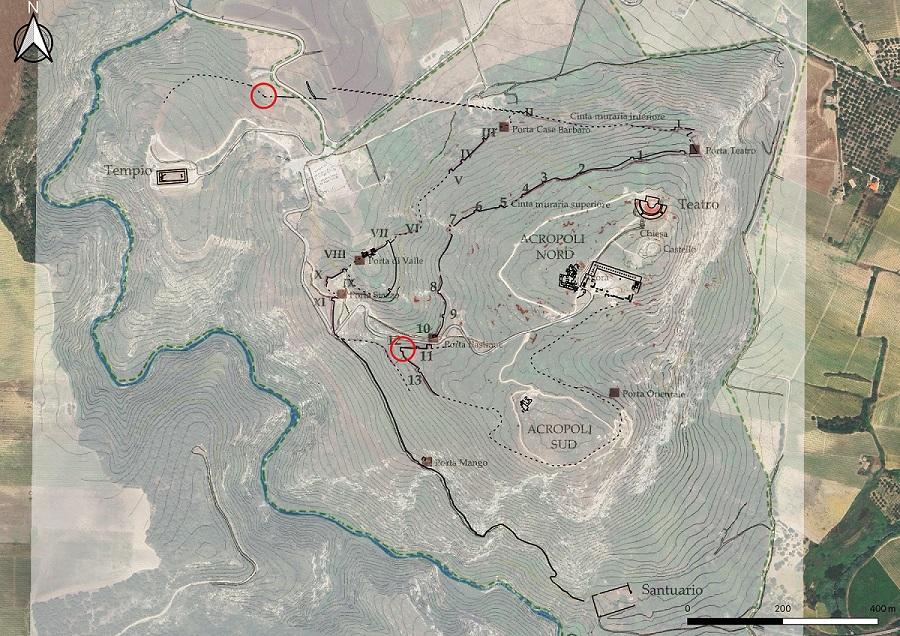

Segesta is the most important center of Elymian people in western Sicily. It played a prominent role in power struggles between the Greeks, Carthaginians, and Romans that took place between the 6th and 3rd century BC. The city is located on top of a steep mountain at 305 m a.s.l. It is particularly known for its well preserved theater and a monumental, unfinished Doric temple (Mertens 1984). Several traits of the city wall that is central for the urban layout and development have been identified and partially explored since the 1980s (Camerata Scovazzo 2008). Based on their course, building technique, and some stratigraphic excavations, a lower city wall with 11 towers and 3 gates has been identified and dated to the 6th/5th century BC, and an upper city wall with 13 towers and 2 gates has been identified and dated to the late 1st century BC. But many questions regarding the city walls remain open, and no comprehensive investigation has been carried out so far.

Therefore, a new project focusing on the city wall has been initiated in 2022, in a cooperation between the Freie Universität Berlin and the Università degli Studi della Tuscia, under the direction of Chiara Blasetti Fantauzzi, Monika Trümper, and Salvatore De Vincenzo. After a brief survey campaign in 2022, a first excavation campaign was carried out between April 1 and 17 in 2025. This project could not be carried out without the generous permission, support, and cooperation of the Parco Archeologico di Segesta. Particular thanks are owed to the director Luigi Biondo. Thanks to the Erasmus+ Staff Mobility for Teaching program we were able to conduct an on-site field school, bringing together students from both universities.

Excavation was concentrated in two areas: first, the northeastern slopes of the hill on which the monumental unfinished temple is located, and second, Tower 12 of the upper city wall (fig. 1). The results were highly promising and confirm the enormous potential of a long-term large-scale fieldwork project on Segesta’s city walls.

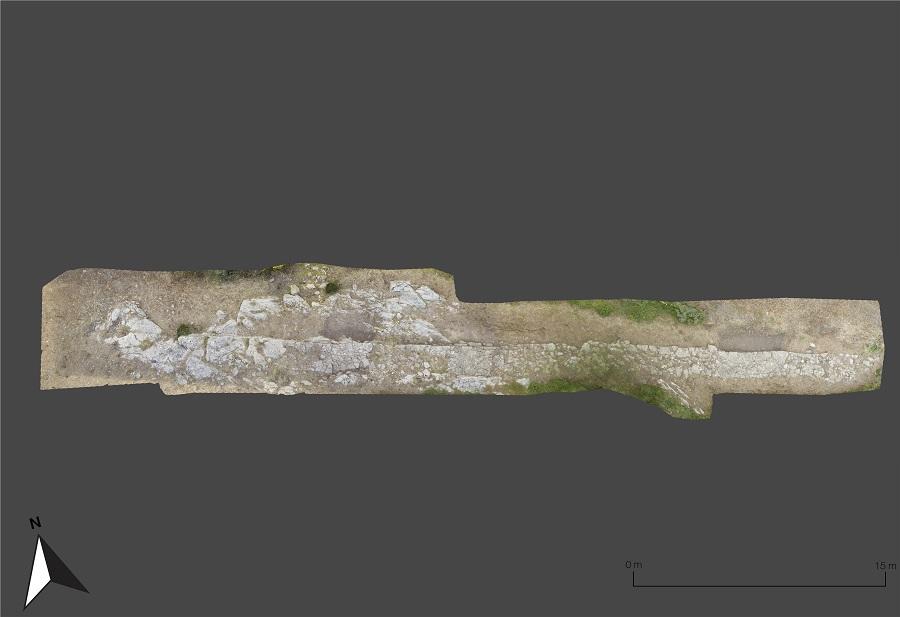

In the first area, Rossella Giglio, at the time director of the Parco Archeologico di Segesta, had carried out investigations in 2003 (Giglio 2016, 2019). She had uncovered a wall 45 m long just to the northeast of the famous temple that seemed to surround the temple hill and was not linked to either the upper or the lower city walls. The wall was found to both sides of the modern street. It was set onto the rock and made of local limestone blocks of different sizes. Giglio had generically dated the wall to the late 6th century BC based on its building technique and the fact that a street was built in the Hellenistic period on top of the razed wall. At the northwestern end of Giglio’s trench, the otherwise strictly straight running wall made a strange bend (fig. 2). A trench was made at precisely this point, first cleaning and reexavating Giglio’s trench and then extending it to the northwest. Furthermore, a large part of the wall (to the west of the modern street) was cleaned and fully documented with various methods (figs. 3. 4). While no strata with diagnostic finds were found in the small trench, it could be clearly determined that the different explored parts of the wall differ remarkably in width, building material, and technique. It is obvious that they belonged to different phases which remain to be determined during more extensive fieldwork in the areas to the west and east of the modern street. Further research is particularly important to clarify crucial questions regarding the date, development, and function of this wall: did this wall surround the entire temple hill; was this a temenos wall, or was the temple hill included into the terrain of the city; and when was the wall built: for a presumed predecessor of the temple (Mertens 1984, 6–8), or when the temple was built at the end of the 5th century BC (Mertens 1984, 202–205); and finally, was the wall repaired or changed, when and why?

The second area at Tower 12 yielded equally promising and unexpected results. Tower 12 has a size of 4 x 7.5 m; its double-faced walls were made with large limestone blocks in the exterior face and medium-sized and small blocks in the interior face. An undisturbed stratigraphy was found inside the tower (trench of 6.5 x 3 m), with fill levels of earth and stones (fig. 5). These fills were removed for a depth of 55 cm. In the southeast corner of the tower, two narrow rubble walls of an earlier building were found, possibly a house that was destroyed when the tower was built. Diagnostic pottery fragments from the fill layers include Dressel 1 amphorae, gray ware, Eastern Sigillata A of Sicilian production, as well as Dressel 2 lamps with red paint, and suggest a terminus ante quem non for the construction of the tower in the mid-1st century BC.

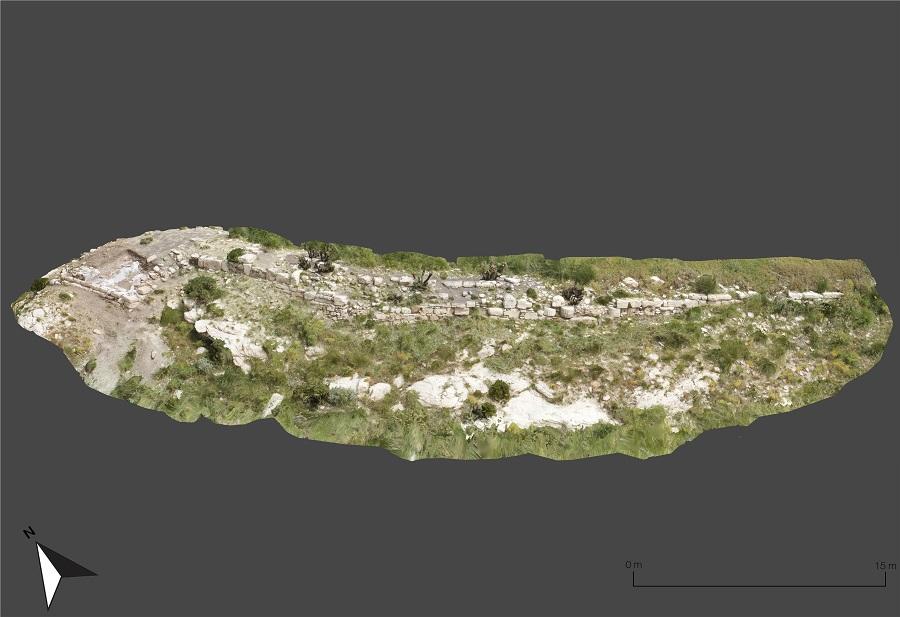

The wall that runs south of Tower 12 was partially cleaned for a length of 30 m (fig. 6). Both the tower and the wall include many reused architectural elements, mostly of the Doric order: fluted and facetted column drums; a sima block with lion water spout; cornice blocks with mutuli and guttae; a Doric capital with an octagonal shaft; thresholds; and others (figs. 7. 8). The size and quality of the elements suggest that they were taken from public buildings, and a preliminary typological comparison shows similarities between the reused elements and the Hellenistic architecture of the theater and agora of Segesta. Among the most significant reused blocks is a fragment of a frieze with a small triglyph flanked by parts of two metopes; a 18-20 cm wide band below the triglyph and metopes includes a Greek inscription (fig. 9). The letters ΟΣΕΓΕ can be clearly identified, standing maybe for ΕΓΕ(ΣΤΑΙΟΙ) or ΕΓΕ(ΣΤΑΙΩΝ). Inscriptions from Segesta mention Ο ΔΑΜΟΣ ΤΩΝ ΕΓΕΣΤΑΙΩΝ (e.g., Ampolo – Erdas 2019, 52–53 ISegesta G4). The new inscription remains to be fully studied, but it may again point to the public sphere. The combination of the frieze of triglyphs and metopes with a (reduced) architrave was quite common in the Late Hellenistic period. Parallels are, e.g., known from the gymnasium (Fiorentini 2009, 75 fig. 6) and the porticus triplex of the Hellenistic-Roman temple (Livadiotti – Fino 2017, 106–107 figs. 9–10) at Agrigento.

Tower 12 is part of the defensive system connected to the so-called Bastion Gate (Porta Bastione), and constitutes the corner tower between that gate and the section of wall that runs southeast along the top of the hill, in the direction of the South Acropolis (Acropoli Sud, fig. 1). These walls were most likely part of a new defensive system surrounding the South Acropolis, creating a kind of fortress in this sector of the city.

The reused blocks and the stratigraphy of Tower 12 suggest that this wall was built in a hurry, in a time of crisis and danger, sometime around the mid-1st century BC. The civil war between Sextus Pompey and Octavian which had a major impact on Sicily may also have affected Segesta and have caused the hasty construction of the South Acropolis wall. A parallel is provided by Cossyra (Pantelleria) where a fortress has recently been attributed to Sextus Pompey and his attempt to use the island as a defensive bulwark, as recorded by Appian (Appian, Civil Wars 5, 97; Capozzoli – Osanna 2009). This fortress was also constructed at the highest point of the city and entailed the destruction of earlier buildings in this area.

Chiara Blasetti Fantauzzi – Monika Trümper – Salvatore De Vincenzo

May 12, 2025

Bibliography

- Ampolo, C. – D. Erdas, Inscriptiones Segestanae. Le iscrizioni greche e latine di Segesta (Pisa 2019)

- Camerata Scovazzo, R. (ed.), Segesta III. Il sistema difensivo di Porta di Valle. Scavi 1990-1993 (Mantova 2008)

- Capozzoli, V. – M. Osanna, Nuovi dati su Cossyra ellenistica: dalla ridefinizione urbanistica di III sec. a.C. alla fortezza di Sesto Pompeo, Siris 10, 2009, 169–209

- Fiorentini, G., Il ginnasio di Agrigento, Sicilia Antiqua 6, 2009, 71–109

- Giglio, R., Segesta. La necropoli ellenistica extra moenia e il muro urbico tardoarcaico (area 15000, SAS 15 area 18000, SAS 18). Rapporto preliminare, Annali della Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa. Classe di Lettere e Filosofia 8, 2016, 37–51, 142–146

- Giglio, R., Il sistema difensivo di Lilibeo e Segesta nella diacronia, Analysis archaeologica. An international journal of Western Mediterranean archaeology 5, 2019, 81–95

- Livadiotti, M. – A. Fino, Il complesso porticato a Nord dell’agora, in: L. M. Caliò et al. (eds.), Agrigento. Nuove ricerche sull’area pubblica centrale (Rome 2017) 97–110

- Mertens, D., Der Tempel von Segesta und die dorische Tempelbaukunst des griechischen Westens in klassischer Zeit (Mainz 1984)

Fig. 1: Segesta, city walls with location of the new excavations (red); Lorenzo Ceruleo, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology

Fig. 2: Trench 1, the northwestern end of Giglio’s trench, Sabatino Martello, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology

Fig. 3: The wall northeast of the temple excavated by Giglio; Lorenzo Ceruleo, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology

Fig. 4: View of the wall excavated by Giglio; Sabatino Martello, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology

Fig. 5: Trench 2, Tower 12; Lorenzo Ceruleo, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology

Fig. 6: SfM 3D model of the wall south of Tower 12; Lorenzo Ceruleo, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology

Fig. 7: Sima block with lion water spout, Jona Winzek; © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology

Fig. 8: Cornice block with mutuli; Jona Winzek, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology

Fig. 9: Fragment of a frieze with a triglyph, parts of two metopes, and Greek inscription; Natalia Meling, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology