Segesta: City Walls and Urbanism

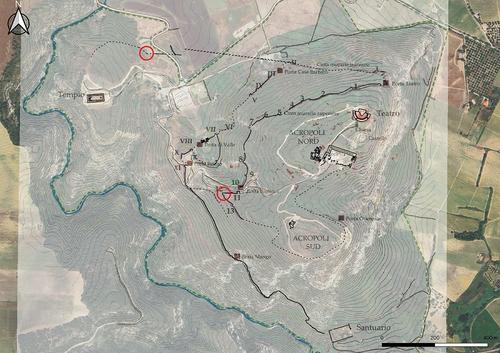

Fig. 1: Segesta, city walls with location of the new excavations (red); Lorenzo Ceruleo, © FU Berlin, Institute of Classical Archaeology_small

Fig. 2. Wall section northwest beyond the lower city wall.

Bildquelle: M. Trümper

Fig. 3. Porta di Valle.

Bildquelle: M. Trümper

Fig. 4. Porta di Valle.

Bildquelle: C. Blasetti Fantauzzi

Fig. 5. Porta di Valle. Oblique UAV photo.

Bildquelle: L. Ceruleo

Fig. 6. Porta di Valle. Oblique UAV photo.

Bildquelle: L. Ceruleo

Fig. 7. Porta Stazzo.

Bildquelle: M. Trümper

Fig. 8. Tower 8.

Bildquelle: C. Blasetti Fantauzzi

Segesta is the most important center of Elymian people and played a prominent role in the historical events that unfolded in Sicily between the Greeks, Carthaginians, and Romans. The history of Archaic Segesta was characterized by repeated conflicts with Selinus, which sought access to the Tyrrhenian Sea (Diod. 5, 9). The first disputes are recorded as early as 580 BC. More than a century later, Diodorus reports a further conflict that took place in 454 BC and led to Athens intervening in favor of the Elymian center in 415 BC (Diod. 12, 82; Thuc. 6, 6). After its alliance with Carthage, Segesta was besieged by Dionysius I of Syracuse in 397 BC (Diod. 14, 48.). The city was later conquered by Agathocles in 307 BC, who changed the name of Segesta to Dicepoli (Diod. 20, 71). However, this conquest was short-lived and Segesta came soon back under Carthaginian control. In 276 BC it formed an alliance with Pyrrhus (Diod. 22, 10) and then switched to the Romans during the First Punic War (Diod. 13, 5). The Romans granted the Elymian center the status of a civitas libera ac immunis (Cic. Verr. 3, 6, 13).

The city is located in western Sicily on top of Monte Barbaro at 305 m a.s.l. Archaeological research focused on the theater, the monumental Doric temple, and the sanctuary of Contrada Mango. Although the city walls are central for the urban layout and development they have received only little attention in research so far, primarily during brief excavations in the 1980s and 1990s (Biagini – Denaro 1995; Favaro – Bechtold 1995; Polizzi 1995; Camerata Scovazzo 1996; Gargini 1999; Vaggioli 1999; Camerata Scovazzo 2008 on the excavation of Porta di Valle undertaken in the 1990s.).

Two city walls were identified mainly based on aerial photos: a lower one with 11 towers and 3 gates and an upper one with 13 towers and 2 gates (fig. 1). Additional wall sections with a gate were identified in the area of the southern acropolis and a single isolated gate near Contrada Mango. A wall section northwest beyond the lower city wall, identified in 1996 and recently excavated, was generally dated to the Archaic period (fig. 2); it has no connection to other sections of the city walls (Giglio 2016, 2019). While the recent excavations in the Agora and in the sanctuary of Contrada Mango have led to a significant revision of the chronologies proposed for these two areas, the (old) chronology of the city walls published in the preliminary reports of the 1990s is still used today for reconstructions of the general development of the city (most recently Ampolo 2022).

Numerous questions regarding the city walls and the urban development of Segesta remain unanswered, however. This includes the development and plan of the identified walls and the city in different historical phases, the relationship and connection of the lower and upper walls, the accessibility, the connection with the surrounding area, the perception of the walls in a diachronic perspective and the viability of the city and the countryside, which is closely linked to the location and importance of the gates. Modern approaches, as developed and applied by the network “Focus Fortification: Ancient Fortifications in the Eastern Mediterranean” (Frederiksen et al. 2016; Müth et al. 2016), landscape studies, and microregional studies (De Vincenzo 2016), have not yet been applied to Segesta and present an opportunity for innovative research perspectives.

In 2022, a new excavation and survey project was initiated by the FU Berlin in collaboration with the Università degli Studi della Tuscia, Viterbo and the Parco Archeologico di Segesta. This project aims to comprehensively investigate the city walls of Segesta from a diachronic perspective with new questions, approaches, and methods. The walls will be cleaned and fully documented, and excavation will be made in important areas. A reliable georeferenced model of the walls will be generated to clarify the layout in relation to the topography, the typology, the chronology, and the construction process including the procurement of building materials. This research project will provide a better understanding of the relationship between the walls, historical events, and the development of Segesta and its surrounding area. The reconstruction of Segesta’s urban development in a long-term perspective will also allow assessing the cultural interactions between the Elymians, Greeks, and Romans as reflected in the plan of the city and its fortifications.

2022

A first fieldwork campaign was carried in August of 2022. It served to check the visibility, accessibility, and preservation of the walls, to test the feasibility of typological studies and appropriate methods for future fieldwork, and to identify areas for future excavations (figs. 3-8).

2025

A second excavation campaign was carried out in April of 2025. It served to test the potential of different methods in two important areas (fig. 1). In these areas, the walls were cleaned, fully documented, and two trenches were carried out.

FUNDING

The project has been generously funded by the Freie Universität Berlin and the Università degli Studi della Tuscia. Thanks to the Erasmus+ Staff Mobility for Teaching program we were able to conduct an on-site field school in 2022 and 2025 in collaboration with the Università degli Studi della Tuscia, bringing together students from both universities.

TEAM

Chiara Blasetti Fantauzzi, Freie Universität Berlin

Salvatore De Vincenzo, Università degli Studi della Tuscia, Viterbo

Monika Trümper, Freie Universität Berlin

This project could not be carried out without the generous permission, support, and cooperation of the Parco Archeologico di Segesta. Particular thanks are owed to the director Luigi Biondo.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ampolo 2022: C. Ampolo, Segesta. Organizzazione civica e spazi urbani, in: C. Ampolo (ed.), La città e le città della Sicilia antica (Roma 2022) 373–397

Biagini – Denaro 1995: C. Biagini – M. Denaro, Tombe tardoantiche di Segesta, Area10000 (SAS 10) e Torre XI, AnnPisa Serie III, Vol. 25, No. 4, 1995, 1153–1157

Camerata Scovazzo 1996: R. Camerata Scovazzo (ed.), Segesta I. La carta archeologica (Palermo 1996)

Camerata Scovazzo 2008: R. Camerata Scovazzo (ed.), Segesta III. Il sistema difensivo di Porta di Valle. Scavi 1990-1993 (Mantova 2008)

Müth et alii 2016: S. Müth – P. Schneider – M. Schnelle – P. D. De Staebler, Ancient fortifications. A compendium of theory and practice (Oxford 2016)

De Vincenzo 2016: S. De Vincenzo, Modelli mediterranei ed elaborazioni locali. Le mura di Erice nel quadro delle fortificazioni del Mediterraneo occidentale alla luce delle indagini stratigrafiche (Roma 2016)

Favaro – Bechtold 1995: A. Favaro – B. Bechtold, Il sistema difensivo di “Porta di Valle”, Area 7000 (SAS 7), AnnPisa Serie III, Vol. 25, No. 4, 1995, 1023–1128

Frederiksen et alii 2016: R. Frederiksen – S. Müth – P. Schneider – M. Schnelle, Focus on fortifications. New research on fortifications in the ancient Mediterranean and the Near East (Oxford 2016)

Gargini 1999: M. Gargini, Le fortificazioni nel vallone NO: la porta (SAS 19). Campagna di scavo 1995, AnnPisa Serie IV, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1999, 87–96.

Giglio 2016: R. Giglio, Segesta. La necropoli ellenistica extra moenia e il muro urbico tardoarcaico (area 15000, SAS15 e area 18000, SAS 18). Rapporto preliminare, Ann Pisa Serie V, Vol. 8, No. 2, 2016, 37–51

Giglio 2019: R. Giglio, Il sistema difensivo di Lilibeo e Segesta nella diacronia, Analysis archaeologica. An international journal of Western Mediterranean archaeology 5, 2019, 81–95

Polizzi 1995: C. Polizzi, Lo scavo dell’area 6000 (SAS6), AnnPisa Serie III, Vol. 25, No. 3, 1995, 1015–1020

Vaggioli 1999: M. A. Vaggioli, Le fortificazioni nel vallone NO (SAS 14, SAS 19). Campagna di scavo 1992, AnnPisa Serie IV, Vol. 4, No. 1, 1999, 57–86