The Visual and Material Culture of British Military Encounters with Egypt, 1798-1918

Between 1798 and 1918, the British armed forces were engaged in a series of major military campaigns in Egypt. Naval victories over the French at the Battle of the Nile (1798) and the Siege of Acre (1799) were followed by a military expedition of over 22,000 troops in 1801-2. Five years later, in 1807, 5000 troops were despatched on a failed campaign in support of Mameluke forces. In 1882, 40,000 men led by Sir Garnet Wolsley formed the British Egyptian Expeditionary Force sent to secure British interests in the region, resulting in British occupation for the next 74 years. In the First World War, Egypt acted as troop camp and training ground for British imperial forces: by 1918 there were as many as 400,000 troops under imperial command in Egypt, including significant numbers of Indian, Australian and New Zealand soldiers.

The extended duration of British military engagement with Egypt and the substantial numbers of troops involved made it an especially fruitful case study for the analysis of militarized cultural encounters. This project examined the perception and experience of Egypt by soldiers of all ranks from Britain and the Empire from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. It drew principally on the National Army Museum and the Imperial War Museum’s rich collections of soldiers’ letters, journals and memoirs, as well as paintings, photographs and souvenirs relating to the Egyptian campaign. It will uncover the dominant topoi and perceptual frameworks through which British soldiers represented their experiences in Egypt. These ranged from the classical to the biblical, from the Christian crusading rhetoric that has been detected in British soldiers’ accounts of the Egyptian campaigns of WW1, to the more touristic view of Egypt summarized in Australian troops’ shorthand ‘sun, sand and syphilis’.

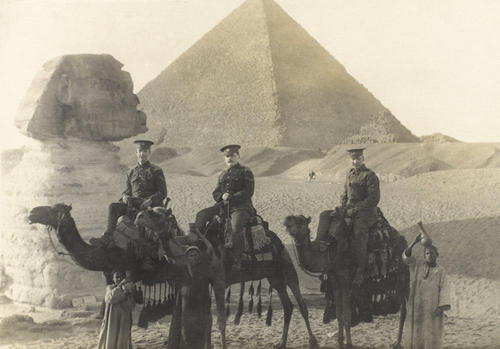

The project focused, in particular, on the visual and material record of this encounter. Firstly, it analysed the rich collection of soldiers’ sketches, engravings and photographs, as well as the visual vocabulary through which the British-Egyptian encounter was represented. The affinity between the ‘tourist gaze’ and the appropriative gaze of the military conqueror had become something of a critical commonplace in studies of both tourism and photography. Little attention, however, had been paid to the visual record of amateur military artists and photographers and how these relate to both forms of military surveillance and touristic and ethnographic modes of viewing. The project looked to develop an analytical framework through which to interpret the culture and practice of amateur military photography setting it alongside other, more familiar, textual records of war experience. Secondly, it explored the curious blending of the local and the ‘exotic’ that resulted from the incorporation of Egyptian symbols such as the Sphinx into British regimental iconographies and traditions. As well as examining how the encounter may have been filtered through these local traditions, it also considered how far Egypt operated as a site in which the transnational affinities of the multi-ethnic British imperial army could be articulated. The Army of India sent an estimated 7,000 troops, including many sepoys, to serve in the Egyptian campaign of 1801-2, while an estimated 144,000 Indian troops were deployed in Egypt and Palestine in the First World War. Finally, it paid close attention to the material culture of the British-Egyptian encounter, exploring how the souvenirs, antiquities and curiosities collected by soldiers functioned as means of self-fashioning and as repositories of memory and meaning. In so doing, the project sought to add new approaches and insights to the burgeoning scholarship on the material culture of warfare.