German Soldiers in Russia, 1812: Introductory Text

by Leighton James

Bavarians in the Battle of Polotsk, 17-18 August 1812

Image Credit: © Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr, Dresden, Germany

Herbert Knötel, depiction of uniform, (1936)

Image Credit: © DHM, Berlin, Germany

Commenting on the centenary of the Russian campaign, the German author and historian, Paul Holzhausen, wrote that there was no campaign that was so ‘abysmally written on the soul of the people. Not the war, which the great Frederick fought with the Austrians, French and Russians, with the finely coiffured Louis XV, with the wild Croats and Pandours of Maria Theresa, not the year of the battle of Leipzig, not the the campaign of Waterloo, not 1870. None’.

He pointed out that one could visit the ‘fields of honour’ of those other campaigns. But not for 1812. ‘Did not return! That was the terrible phrase that passed through thousands of German families, that was related by tearful fathers, mothers, sisters and brides’.

Some, however, did return, in 1813 ragged and exhausted. Others returned years later after the war, eventually released from captivity. These fortunate veterans found an audience eager to vicariously experience the Russian campaign through their accounts. The decades after 1812 saw the publication of several veterans’ memoirs. These accounts not only memorialised the conflict, but also contributed to the construction of a German view of Eastern Europe.

On 24 June 1812 Napoleon’s Grande Armée began crossing the Niemen river and entering Russian territory. The invasion marked the opening phase of a campaign which would result in not far short of 400,000 total military losses and the burning of Moscow. In 1807 Napoleon and Tsar Alexander I had embraced on a raft in the river Niemen, but thereafter Franco-Russian relations had deteriorated. In 1810 the Tsar protested Napoleon’s annexation of the North German coast and issued a ukase (decree with force of law) on 31 December 1810 which opened Russian ports to neutral trade, while banning the importation of French goods. Napoleon could not tolerate this open challenge to his Continental System designed to undermine the British war effort and began preparing for an invasion of Russia. To do so he assembled a vast army. Estimates of the size of the force range from 450,000 to 675,000 men. Amongst the army were also thousands of civilians. These included soldiers’ wives and their children, camp followers, servants and sutlers. The soldiers themselves were drawn from across western and central Europe. Alongside the French marched Belgians, Spaniards, Portuguese, Italians, Swiss, Croats and Germans. In fact, if we include the troops recruited directly into the French army from the annexed territories along the left bank of the Rhine, there were more Germans than Frenchmen in this army. The German states of the Confederation of the Rhine committed nearly 100,000 troops. The largest contingent was provided by the Kingdom of Bavaria, which supplied some 30,000 soldiers. Saxony provided 25,500, Württemberg 15,000, the Grand Duchy of Baden 7,000, and Mecklenburg, 1,700. The satellite states created by Napoleon, the Kingdom of Westphalia and the Grand Duchy of Berg, supplied 25,000 and 5,000 troops respectively. To these can be added the 20,000 Prussians operating to the north and 20,000 Austrian troops to the south of the main line of march. These soldiers were readily identifiable by their uniforms of various colours, predominantly shades of blue with red accents and green for Jäger regiments, cornflower for the Bavarians and white/gray trousers for the Saxons.

Albrecht Adam (1786-1862), On the road to Lianvawitschi ("Sur la route vers Lianvawitschi le 14 Aout"), (1812)

Image Credit: © BayHStA, Munich, Germany

Supply problems began almost immediately. Napoleon had ordered the preparation of large supply depots on Polish territory. Some 25,000 wagons and 90,000 animals hauled ammunition, food, portable ovens and mills forward. Herds of livestock were also driven the wake of the army. The poor condition of the Russian roads, however, made bringing the goods up to the army difficult and the supply train could not keep pace with the advancing troops. Inadequate supplies meant that the troops had to fall back on foraging from the local countryside. Russia, however, was sparsely populated and villages often far removed from each other. The Russian army also adopted a scorched earth tactic as it retreated in face of the Grande Armée, stripping the land of supplies and burning villages in its wake. Supplies were difficult to find in this devastated landscape and foraging parties were forced to range further and further afield. Desperation, fear of attack by partisans or Cossack bands and a belief in the semi-civilised nature of the Russians drove extreme violence by the soldiers. Tales of pillage, rape and the desecration of churches were common. Attempts were made to curb the pillaging by executing perpetrators, but these actions had little impact in the desperate circumstances. Desertion and suicide were commonplace.

The story of the devastating impact of the Russian winter on the Grande Armée is well known. Less well known was the debilitating nature of the Russian summer, particularly to new recruits unused to the rigours of campaigning. High temperatures, strenuous marches, and inadequate supplies and shelter weakened the constitution of the soldiers. Thousands fell prey to diseases, such as dysentery and typhus, which ran rampant among the exhausted and poorly supplied soldiers.

Napoleon was unable to find the decisive victory he sought. The Grande Armée clashed with the Russians at Smolensk on 17 and 18 August and at Borodino on 7 September. The latter was amongst the bloodiest battles of the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon’s army suffered 30,000-35,000 casualties, some 22 per cent of his force. The Russians suffered more, between 40,000 and 50,000 casualties, but managed to retreat in good order.

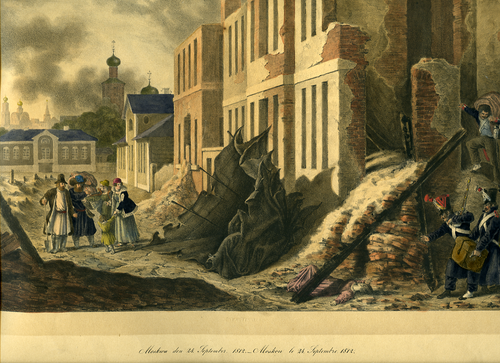

Napoleon entered Moscow on 14 September to find a largely deserted city. Most of the inhabitants had fled once it became clear that the city would not be defended. On 15 September fires set partially by Russian saboteurs and partially by looting soldiers took hold [Int. ID: 320478]. Soon much of the city was ablaze and Napoleon was forced to temporarily abandon the Kremlin. The blaze continued for three days and ravaged large parts of the city.

Napoleon dispatched repeated messengers to Tsar Alexander requesting negotiation, but all were turned away. On 13 October the first snows fell. Concerned over his extended supply lines and fearing being cut off, Napoleon took the decision to retreat to Smolensk. The retreat began on 19 October, initially along a route to the south. A costly victory at Maloyaroslavets, however, convinced Napoleon to return along the original route of march, crossing territory already devastated and denuded of supplies.

Diary of a cavalryman from the Russian war (title page), Franz von Sauer, (1812)

Image Credit: © BayHStA, Munich, Germany

Christian Wilhelm von Faber du Faur (1780-1857), Russian citizens between rubble and soldiers from the 3rd French army corps during the looting in Moscow on September 24, 1812

Image Credit: © DHM, Berlin, Germany

On 26 October the temperature began to fall. Houses and barns were torn down to supply firewood. Exhausted soldiers risked falling into the flames and being badly burnt. War booty taken from Moscow was abandoned by the roadside, as were many of the wounded. Russian prisoners of war that fell behind were shot. On 29 October the head of the retreating army reached the battlefield of Borodino, still littered with bodies and the debris of war.

The army reached Smolensk in November, but the stockpiles of supplies were quickly looted by the starving troops. The temperature continued to fall to between minus 15 and minus 25 Celsius. Heavy snowfall now hampered the retreat. Starving men fell on the carcasses of horses in search sustenance and cut strips of flesh from living animals in their desperation. Under these circumstance discipline broke down as soldiers banded together by national and regional identity.

Stragglers or those forced off the road in search of supplies risked being captured and killed by Cossacks and armed peasants. Many were immediately killed or died as a result of exposure after being stripped of their clothing. Cossacks sold prisoners to peasants to be killed. Such activities fuelled perceptions of the Russians as savage and uncivilised. Of the 90,000 to 100,000 prisoners were taken by the Russians, only around 39,000 survived they captivity. Those fortunate to survive their capture were sent to the interior of Russia, some to return home years after.

The suffering of the army intensified at the crossing of the river Berezina. Dutch engineers, working in freezing temperatures, had constructed a pontoon bridge across the river. While Marshals Oudinot and Ney, fended off Russian troops on the west bank, and Marshal Victor did the same on the east, the remnants of the army began to cross on 28 November. The Russian General, Wittgenstein, however, brought his cannons within range of the bridge. Memoirs describe a terrifying scramble to cross the bridge. Men, women and children were crushed in the press, trampled underfoot or drowned in the freezing water. As the Russians approached the bridge was fired. Desperate stragglers sought to cross the burning bridge or tried to swim across. Some 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers were killed, wounded or captured, along with some 10,000 to 30,000 civilians.

The suffering continued in the twelve-day march from the Berezina to Vilnius. Those soldiers that fell by the wayside were stripped by their former comrades, sometimes while still alive. Theft was commonplace. Fighting broke out and acts of murder occurred as the soldiers struggled to survive.

The suffering of the army was compounded by division in the command. On 5 December Napoleon left the army to return to Paris. He turned over command to Marshal Murat, but the Marshals were soon at odds. Unable to impose order, Murat handed over command to Eugène de Beauharnais and abandoned the army. He was followed by the rest of the Marshals. The lack of clear command and organization meant that the supplies stockpiled in Vilnius, like those at Smolensk, were quickly looted.

The retreat ended on 23 December when the Imperial Guard entered Königsberg. The losses had been devastating. Although the Prussian and Austrian contingents had escaped relatively intact, of the main force only some 38,000 recrossed the Niemen. Participants continued to die into 1813 as a consequence of wounds and disease. The German contingents were decimated. Of the 25,500 Saxons and 30,000 Bavarians who marched into Russia, 6,000 and 3,000 returned respectively. The losses of other Confederation of the Rhine troops were even higher. Only 250 Westphalian, 118 Mecklenburg and 500 Württemberg soldiers returned.

Bibliography

- Adams, Michael. Napoleon and Russia. London ; New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2006.

- Austen, Paul Britten. 1812 : Napoleon in Moscow. Pen and Sword, 2012.

- Forrest, Alan I./Karen Hagemann (eds.): War memories. The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars in Modern European Culture, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

- Holzhausen, Paul. Die Deutschen in Russland, 1812: Leben und Leiden auf der Moskauer Heerfahrt. Morawe & Scheffelt Verlag, 1912.

- Lieven, D. C. B. Russia against Napoleon: The True Story of the Campaigns of War and Peace. New York: Viking, 2010.

- Murken, Julia. Bayerische Soldaten Im Russlandfeldzug 1812. Ihre Kriegserfahrungen und deren Umdeutungen im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert. München: Beck, 2006.

Citation

James, Leighton: German Soldiers in Russia, 1812. Introductory Text to the Exhibition of www.mwme.eu (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---