The Cossacks in the Memoirs of German Soldiers in the Grande Armée

by Leighton James

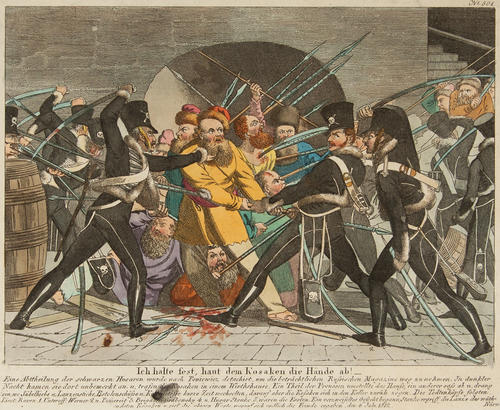

“Cut off the Cossack‘s hands“

Image Credit: © Militärhistorisches Museum der Bundeswehr, Dresden, Germany

The figure of the Cossack looms large in the memoirs of German soldiers of the Russian Campaign. Initially, the Cossacks were a people inhabiting the lower Dnieper, Don and Ural river basins. In the early modern period they had allied themselves to the Russian Tsars and had played a key role in the extension and subjugation of the imperial frontiers. The Cossacks had become a special military estate within Russian society by the end of the eighteenth century. The relationship had, however, often been tense. Russian attempts to control and reduce the autonomy enjoyed by the Cossacks hosts had led to episodic revolts, the most recent and serious the Pugachev rebellion of 1773-1775. These rebellions had been bloodily suppressed by Russian imperial forces, but deep suspicion characterised the Russian elite’s view of the Cossacks on the eve of the 1812 campaign.

The campaign was ‘to be one of the defining events of the nineteenth century for the Cossacks’ (O’Rourke: p. 138). During 1812 the number of Cossacks was swelled by an appeal for volunteers to face the invader. Twenty-two militia regiments were formed in response to this appeal. The militia regiments were joined by four regular Cossack regiments already in the Don region. Through forced marches they met with the main Russian army under the command of General Kutuzov in October. A potent mixture of patriotism, xenophobia, promises to restore the old privileges and the chance of enrichment through looting the Grande Armée swelled the Cossack ranks to somewhere between 16,000 and 20,000 by mid-October 1812. Although the Cossacks operated alongside the regular Russian cavalry, they really distinguished themselves as light, irregular cavalry. Often operating behind enemy lines, they provided the Russian army with vital reconnaissance during the campaign whilst disrupting the Grande Armée’s lines of communication. They also swept down on stragglers from the Grande Armée, supply columns and foraging parties. The operations of the Cossack bands thus made foraging a dangerous activity for the soldiers of the Grande Armée. This compounded the logistical problems already caused by extended supply lines and the Russian’s scorched earth policy that beset Napoleon’s forces. Cossacks also provided a link between the regular Russian military and the partisan bands that emerged in the course of the campaign. In some instances they operated alongside the partisans, such as the band led by Lieutenant-Colonel Denis Davidov.

The soldiers of the Grande Armée became particularly vulnerable to the Cossacks as military discipline and unit cohesion began to break down after the crossing of the Berezina. Small, isolated groups had little chance of withstanding Cossack raids, a fact frequently commented on in soldiers’ memoirs. Karl von Suckow, an officer in the Württemberg army claimed that a new word was coined in response to the Cossack threat - kosakiert (cossacked). Sucks recalled that the mere cry, ‘Cossacks!’, was sufficient to induce panic amongst the German and French soldiers during the retreat from Moscow.

Cossacks were also feared for their wild and unpredictable nature. As mostly irregular troops, Cossacks were not regarded as bound by the same ‘laws of war’ as the regular military. There was little expectation that requests for ‘pardon’ would be respected by the Cossacks. Nor did the Cossacks appear to respect rank or social status. Most encounters with Cossacks involved the swift and efficient robbery of captured soldiers. Many memoirists recall captives being stripped even of their clothing, leaving them exposed to the elements. However, some memoirists wrote that it was better to be captured by the Cossacks than to fall into the hands of the armed peasantry. The former would rob prisoners of war, but the latter were accused of torturing and mutilating captives. Some memoirists claimed that the Cossack bands were not above selling prisoners of war to armed peasant groups.

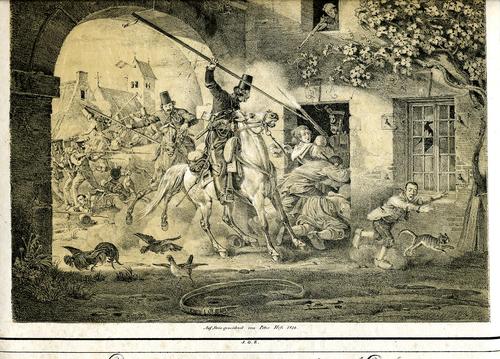

Peter von Hess, Don Cossacks take a French village by surprise (1818)

Image Credit: © DHM, Berlin, Germany

Despite their reputation for savagery, some memoirists also remembered acts of kindness from the Cossacks. One soldier, for example, recalled the fate a pregnant soldier’s wife, captured alongside her husband. The pregnant woman was given a horse to ride and treated with the utmost care. Others were treated well because they possessed a skill that their captors valued. Karl von Schehl was better treated than his fellow prisoners because he was able to play the trumpet.

The image of the Cossack presented in the memoirs is, therefore, that of an implacable, almost omnipresent threat. It is possible that the German soldiers that marched into Russia already had an image of the Cossacks formed in their imagination. Cossacks had been deployed by the Russian military in German Central Europe during the Seven Years’ War and they appear to have left behind a reputation for rapine, wildness and violence. Dieter Kienitz has indicated the ‘the reports of the behaviour of the Cossacks in the Seven Years’ War had left the public with the impression that they were nothing more than plundering and murderous barbarians from the East’ (Kienitz: p. 11). Indeed, for the ‘Western Europeans, above all the Germans, the concept of the Cossack was bound up with a terrible images (Schreckensbilder) of torturing, robbing, looting and murderous barbarians’ (Kienitz: p 43). The soldiers’ memoirs did little to counter this image, but rather tended to reinforce it.

The images would shift somewhat as a consequence of the 1813 campaigns. Cossacks now campaigned in Central Europe against the French. Katherine Aaslestad, for example, has identified a ‘Cossackmania’ in parts of northern Germany in the 1813, as the educated public sought to understand the culture of their liberators from French hegemony. This manifested itself in a craze for Cossack costume, music and that was enthusiastically, if briefly, embraced by parts of the German public (Aaslestad: p. 284). The fascination with the Cossack spread beyond Germany to other European states, such as Britain. The figure of the Cossack appeared in many European prints and caricatures in between 1812 and 1815. Yet, this print culture also emphasised the exoticism of the Cossack. This was projected against the background of civilised Europe, such as the streets of European cities like Paris or their terrifying presence in a French village. Often the positive interest in Cossack culture was short-lived as the demands of war meant that they, like all armies, quickly became a burden on the local population.

Undoubtedly the reputation the Cossacks gained during the Seven Years’ War coloured the expectations of German soldiers in 1812. Their seemingly savage nature was heightened by the circumstances of the retreat from Moscow. Despite the brief interest in wider Cossack culture created by the military and political circumstances of 1813, they remained a shorthand for the uncivilised nature of Eastern Europe.

Sources

- Scheel, Karl von: Vom Rhein zur Moskva 1812 (Krefeld: Richard Obermann, 1957)

- Suckow, Karl von: Aus meinem Soldatenleben (Stuttgart: Adolph Krabbe, 1862)

Bibliography

- Aaslestad, Katherine: Place and Politics: Local Identity, Civic Culture, and German Nationalism in North Germany during the Revolutionary Era (Leiden: Brill, 2005)

- Kienitz, Dieter: Der Kosakenwinter in Schleswig-Holstein 1813/14: Studien zu Bernadottes Feldzug in Schleswig und Holstein und zur Besetzung der Herzogtümer durch eine schwedisch-russisch-presussiche Armee in den Jahren 1813/14 (Heide: Boyens, 2000)

- O’Rourke, Shane: The Cossacks (Manchester: MUP, 2007)

Citation

James, Leighton: The Cossacks in the Memoirs of German Soldiers in the Grande Armée (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---