Germany and Jihad

by Samuel Krug

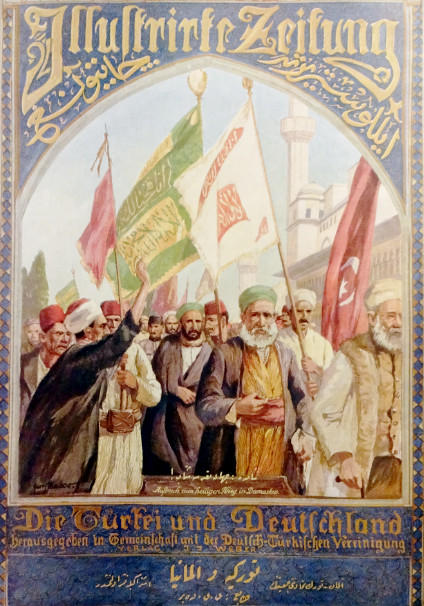

'Illustrirte Zeitung‘, Special Edition ‘Die Türkei und Deutschland’ No.3803, 18. May 1916, title illustration adapted from a painting by Georg Macco (1863-1933)

Image Credit: Personal collection, Photo: Oliver Stein

In the first week of November 1914, the Triple Entente declared war on the Ottoman Empire. A few days later, on November 14, Turkish religious authorities presented five short fatwas (legal opinions) during a public ceremony in Istanbul. The event came to be known as the Ottoman jihad proclamation against Russia, France and the United Kingdom. The call to arms addressed the followers of Islam worldwide with two simple messages: fighting the enemies of the Ottoman Empire is a religious duty for all Muslims and harming allied forces is a great sin.

Contemporaries insinuated a German involvement in the declaration. In this view, Germans invented the utilization of jihad for the means of war and non-European actors were merely bystanders. The present-day scholarly debate revolves around Muslim agency in the attempt to politicize the jihad concept in WWI. Three arguments can be made here: firstly, when European Powers used Islamic rhetoric, for example in colonial contexts, they still had to rely on Muslims for the distribution and application of the concept. Secondly, the Ottoman Empire had its own intentions for using a religious approach; by appealing to religious sentiments, the Sublime Porte tried to weaken anti-Ottoman nationalist movements in the Arab world. Thirdly, the Ottoman Empire frequently used religious rhetoric – and to some extent the jihad concept – before the outbreak of the war, for example during the Crimean War (1853-1856) and the Italian-Turkish War (1911-1912).

German Jihad Propaganda

Still, German politicians and intellectuals were under the impression that jihad would be a practical tool for the German Reich in fighting the Triple Entente. They hoped that uprisings in the colonies and defecting Muslim soldiers would weaken the enemy’s military forces and withdraw units from European battlegrounds. Therefore, the promotion and globalization of a political jihad concept would be necessary. A simplistic view of Islam, which ignored ethnic and cultural diversities, led German decision-makers to believe that a proclamation by the Ottoman Sultan-Caliph would be binding for Muslims from North and Sub-Saharan Africa to India, the Balkans and the Caucasus.

Proponents of the insurrection plan came from different fields: they were officials from the Foreign Office, such as Arthur Zimmermann (1864-1940), and the General Staff, such as Rudolf Nadolny (1873-1953). Kaiser Wilhelm II. (1859-1941) himself favored the idea. Public figures as the journalist Ernst Jäckh (1875-1959), the scholar Martin Hartmann (1851—1918) and the former diplomat Max von Oppenheim (1860-1946) encouraged the “jihadization” too. Amongst others, these actors worked together on different governmental and non-governmental levels in order to achieve their goal. The propaganda organization “Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient” played an important role, as it was a central juncture for supporters from different fields. The cooperation with non-Germans, especially with North Africans, Indians and Turks, was indispensable. They produced texts and circulated the jihad concept amongst other Muslims. Yet, the German government did not confine itself to the publication of propaganda material. Scholars as well as military and diplomatic personnel travelled around countries with significant Muslim populations in order to incite turmoil. While Wilhelm Waßmuß (1880-1931) went to Afghanistan and Mesopotamia, Curt Prüfer (1881-1959) travelled to North Africa and the Levant, Paul Schwarz (1867-1938) visited the Caucasus and Leo Frobenius (1873-1938) tried to reach the Sudan.

While parts of the political and intellectual elite were in favor of the military cooperation with the Ottoman Empire and the promotion of jihad, the majority of Germans were rather skeptical. Missionaries, like Joseph Froberger (1871-1931), feared that the jihad proclamation would strengthen Islam and weaken their missionary endeavor. Colonial administrators questioned the declaration’s results on Muslims in German East Africa and speculated that it could backfire. Even within the Foreign Office, officials such as Friedrich Rosen (1856-1935) disapproved. Yet resistance came mainly from abroad. In 1915, a debate between Carl Heinrich Becker (1876-1933) and Christiaan Snouck Hurgronje (1875-1936) began in which Hurgronje, a Dutch Orientalist and former colonial official, published an article entitled “Heilige Oorlog [Holy War] made in Germany”. He criticized German foreign politics and Orientalists for supporting and promoting jihad. Furthermore, Hurgronje accused Germany of having pushed the Ottoman Empire to the jihad proclamation. According to him, the declaration itself would set the Muslim world back to the Middle Ages. Additionally, European powers have a civilizing mission and should therefore not encourage religious fanaticism. Becker responded promptly, negating German involvement, defending German-Turkish friendship and attacking Hurgronje personally. In his view, jihad had become a secularized concept. The debate went on for several months and resulted in an alienation of the two colleagues due to their fixed viewpoints.

However, a general division between jihad supporters and opponents does not fully recognize the complexity of the topic. Different actors had very different perspectives and intentions for choosing one “side”. Even supporters could disagree on the implementation of jihad or on the concept itself. Two examples can illustrate contrasting views.

Examples

The first example is a booklet written by Eugen Mittwoch (1876-1942) in 1914. Mittwoch was an Orientalist, who taught at the University of Berlin and the Berlin School for Oriental Languages (Berliner Seminar für Orientalische Sprachen) while working for the “Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient”. His publication “Deutschland, die Türkei und der Heilige Krieg” (Germany, Turkey and the Holy War) appeared as #17 in the series “Kriegsschriften des Kaiser-Wilhelm Dank”. For the scholar, Germany is fighting a Holy War, as it is a righteous war. The Ottoman Empire is also fighting a righteous war, because it is fighting for its own existence. In this sense, Mittwoch declares that the Ottoman jihad is not a religious war but a war for national sovereignty. The Turkish government merely adopted the religious concept in order to unite its (Muslim) subjects.

The second example is a brochure from 1915 by Salih ash-Sharif at-Tunisi (1869-1920), who was a religious scholar of North African origin. The text is a translation of an Arabic version from 1914. Entitled “Die Wahrheit über den Glaubenskrieg” (The Truth about the War of Belief), the brochure relies on religious arguments. As the attack on Islamic lands, i.e. the Ottoman Empire, is an act of hostility towards Islam as a whole, it is the personal duty of all Muslims to enter the fight. The religious scholar emphasizes that this particular jihad is not directed against all non-Muslims but only against Russians, French and English.

Both texts understand “Holy War” not only in its historical, literal sense, but see it as a war against unrighteous enemies. Yet, Mittwoch focuses primarily on political matters, while ash-Sharif treats jihad as an exclusively religious category. Interestingly, ash-Sharif’s brochure was published by the “German Society for Islamic Studies”, which sought to advertise the cooperation between the German Reich and the Ottoman Empire.

Conclusion

Neither the Ottoman jihad proclamation nor the German jihad propaganda changed much for the developments of World War One. Istanbul and Berlin were too far away for Muslims in French West Africa or the Indian subcontinent. Turkish and German officials’ assumption that a declaration issued in the Ottoman Empire would indeed be globally binding was a misconception; the cultural and ethnic differences were too significant. The German foreign policy in the “Orient” generally lacked thorough knowledge: emissaries quite often were unfamiliar with local customs and acted in manners that exposed their ambitions to their enemies. Furthermore, although it was state funded, the German jihad propaganda initiative had financial problems.

During the Weimar Republic, German foreign policy lost interest in the Middle East and over thirty consulates were closed. Only in Nazi Germany did the region once again become an issue and some voices tried to bring the old idea of “revolutionizing the Orient” back on the table. However, in these proposals, Islam and jihad did not play a role anymore.

Sources

- At-Tunisi, Ṣaliḥ Ash-Sharif, Die Wahrheit über den Glaubenskrieg, Berlin 1915.

- Mittwoch, Eugen, Deutschland, die Türkei und der Heilige Krieg, Berlin 1914.

Bibliography

- Aksakal, Mustafa, 'Holy War Made in Germany?'. Ottoman Origins of the 1914 Jihad, in: Haldun Gülalp, Günter Seufert (Hg.), Religion, Identity and Politics. Germany and Turkey in Interaction, Hoboken 2013, pp 34–45.

- Habermas, Rebekka, Debates on Islam in Imperial Germany, in: David Motadel (ed.), Islam and the European Empires, Oxford 2014, pp 233–255.

- Heine, Peter, C. Snouck Hurgronje versus C. H. Becker. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der angewandten Orientalistik, in: Die Welt des Islams 23/24 (1984), pp 378–387.

- Kröger, Martin, Revolution als Programm. Ziele und Realität deutscher Orientpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Wolfgang Michalka (ed.), Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wirkung, Wahrnehmung, Analyse, Munich, Zürich 1994, pp 366–391.

- Loth, Wilfried; Hanisch, Marc (ed.), Erster Weltkrieg und Dschihad. Die Deutschen und die Revolutionierung des Orients, Munich 2014.

- Lüdke, Tilman, Jihad made in Germany. Ottoman and German propaganda and intelligence operations in the First World War, Münster 2005.

- Müller, Herbert Landolin, Islam, gihad ("Heiliger Krieg") und Deutsches Reich. Ein Nachspiel zur wilhelminischen Weltpolitik im Maghreb 1914–1918, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1991.

- Pesek, Michael, Für Kaiser und Allah. Ostafrikas Muslime im Grossen Krieg für die Zivilisation, 1914–1919, in: SGMOIK bulletin 19 (2004), pp. 9–18.

- Schwanitz, Wolfgang G., Djihad "Made in Germany". Der Streit um den Heiligen Krieg 1914–1915, in: Sozial.Geschichte 18/2 (2003), pp. 7–34.

Citation

Krug, Samuel: Germany and Jihad (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---

Samuel Krug, M.A. (Freie Universität Berlin)

Mr. Krug is a PhD candidate at the Freie Universität Berlin and works since 2015 on the 'Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient'.