German Soldiers and the Scientific Investigation of the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1918

by Oliver Stein

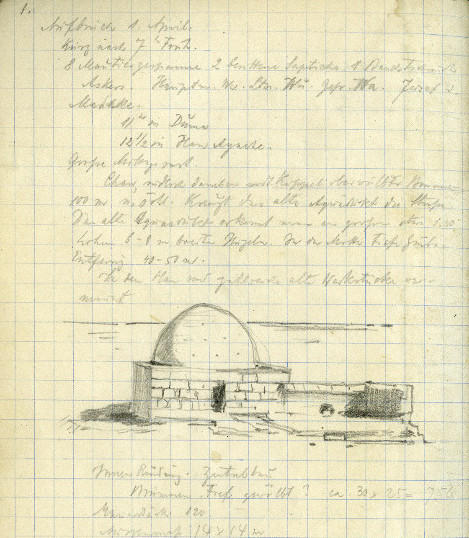

Excavation diary of Lieutnant Carl Wulzinger

Image Credit: © Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Berlin, Germany

Long before the First World War, the landscape of the Ottoman Empire had been a point of interest for many different disciplines of Western research. While the outbreak of war interrupted the majority of civil research, diverse German military-initiated projects replaced this research during the war.

Before the First World War, German officers active as geographers and cartographers had already been working in addition to civil researchers to scientifically analyze the Ottoman landscape. Turkish authorities, however, frequently put strict limitations in place that impeded research within their territories. In the autumn of 1914, when the Ottoman Empire joined the war on the side of the Central Powers, and when a subsequent stream of German soldiers entered the country, German research was suddenly introduced to many novel perspectives. Germans who were well acquainted with the Middle East, among them many researchers, came to the Ottoman Empire as members of the army and often found time on the side of their service for the continuation of their research. Increasingly, military agencies deployed researchers in uniform to the Ottoman Empire for assignments, which were created under the demands of war. For instance geologists traveled in the desert in order to find water for the troops’ sustenance, while military doctors researched epidemics to then determine health measures to protect soldiers. The needs of the war, however, also often served as catalysts for scientific research, which ultimately proved to have benefits beyond military needs. A few examples from different disciplines will help to illustrate this:

Military physician Ernst Rodenwaldt, for instance, after establishing contacts with significant Turkish officials during his successful malaria expedition, was offered the opportunity to build a German research institute in Smyrna after the war. The cooperation between the Germans and Turks, necessitated by war, became the motor for the Germans’ scientific activities within the Ottoman Empire. In result a significant knowledge transfer took place in many fields. This can be illustrated, for example, when the German military meteorologists not only measured the climatic conditions in the Middle East but also built an Ottoman weather service upon the request of Enver Pascha.

Germans also had their own economic interests in mind as they carried out their research in the Ottoman landscape. German geologists in uniform wandered through the land in search of coal and oil resources as well as other rich mineral deposits. This was partially in service of an immediate exploitation for the needs of war, but the knowledge gained was intended to be far more beneficial to the German economy following the war years.

Aside from the researchers deployed for war-related purposes or for economic-political interests, there were also research measures that were purely in service of science, without a direct application or use. The military leadership not infrequently supported even these kinds of studies. Occassionally the responsible officers did not shy away from “dressing the scientific work in military clothes”, as one German admiral put it. The most extensive purely scientific undertaking was the service of the Deutsch-Türkisches Denkmalschutzkommando (monument protection commando) under the leadership of Captain Prof. Theodor Wiegand. The German archaeologists of this unit enjoyed nearly ideal working conditions that they never would have had during times of peace. They not only received help from engineers, but the Prussian Ministry of War also issued a directive to all German aircraft units in the Ottoman Empire to support the archaeologists by taking systematic aerial photos of historical sites: this was the first time that aerial archaeology was used on a large scale.

All in all, the German military played a central role during the First World War for the research activities in the Ottoman Empire - partly as an initiator, and partly as a supporter. The fact that, despite the war, also those investigations were sponsored whose research-related interests outweighed a more utilitarian purpose, is due to both the researchers’ networking with state and military authorities, as well as to the promise of national prestige, which could be won through a science like archeology on a competitive international stage. The apprehension that the Turks would close their lands to further scientific research after the war reinforced the view that research pursuits should take advantage of the wartime as much as possible. In this sense, the uniform consistently proved to be the “best piece of equipment” for the scientists during their undertakings. This uniform was useful in opening many doors with the native population and the Turkish authorities.

Despite this, however, the relationship with the Turks was generally ambivalent in regards to the German research measures. On the one hand, Turks willingly accepted German research in the Ottoman landscape that they themselves could profit from. On the other hand, however, they were constantly concerned that they were being taken advantage of by the Germans. As the German interest in mineral resources can attest, this skepticism on the side of the Turks was not entirely unjustified. Yet seen as a whole, the scientific activity in the Ottoman Empire, with all of its self-interests, did not amount to a politic of exploitation. Regarding their research activities during the war, the Germans took great care to keep the Turks in consideration, as they wanted to avoid action that would potentially upset the alliance.

German research in the Ottoman Empire between 1914 and 1918 proved to have substantial results. Years after the war, German scientists were still able to reap the benefits of their wartime research and publish their work, when access to the Ottoman landscape was denied.

Scientists in uniform even during the war had the chance to find outlets for the dissemination and popularization of their research topics. They held lectures in officers’ messes and soldiers' boarding houses and wrote articles for army journals. In this way, they were able to reach an audience that they never would have had access to during peace times. After the war the veteran’s association for German soldiers serving in the Ottoman Empire - the Bund der Asienkämpfer - opened itself to non-military so called friends of the Orient, particularly Orientalists. Additionally, the association’s bulletin partially adopted the character of an orientalist scientific journal. These facts powerfully exemplify how German military and research in the Ottoman Empire had entered into a kind of symbiosis.

Bibliography

- Alt, Albrecht: Aus der Kriegsarbeit der deutschen Wissenschaft in Palästina, in: Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästinavereins 43 (1920), pp. 93–108.

- Hauser, Stefan R.: Deutsche Forschungen zum Alten Orient und ihre Beziehungen zu politischen und ökonomischen Interessen vom Kaiserreich bis zum Zweiten Weltkrieg, in: Deutschland und der Mittlere Osten, hrsg. von Wolfgang G. Schwanitz (=Comparativ, vol. 14), Leipzig 2004, pp. 46-65.

- Mit Feder und Schwert. Militär und Wissenschaft - Wissenschaftler und Krieg, hrsg. von Matthias Berg, Jens Thiel und Peter Th. Walther, Stuttgart 2009.

- Moreau, Odile: Les ressources scientifiques de l’Occident au service de la modernization de l’armée ottoman (fin XIXe – début XXe siècle), in: Science modern et pouvoir, entrre l’Orient et l’Occident, XIXème-XXème siècle, numero thématique de la Revue des Mondes Musulmans et de la Méditerranée, No. 101-102, Aix-en-Provence 2003, pp. 51-67.

- Trümpler, Charlotte: Das Deutsch-Türkische Denkmalschutz-Kommando und die Luftbildarchäologie, in: Das große Spiel. Archäologie und Politik zur Zeit des Kolonialismus (1860–1940), hrsg. von Charlotte Trümpler, Essen 2008, pp. 474–483.

- Wallach, Jehuda L.: Anatomie einer Militärhilfe. Die preußisch-deutschen Militärmissionen in der Türkei 1835–1919, München 1976.

- Watzinger, Carl: Theodor Wiegand. Ein deutscher Archäologie (1864-1936), München 1944.

Citation

Stein, Oliver: German Soldiers and the Scientific Investigation of the Ottoman Empire, 1914-1918 (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---

Translated by Westrey Page (Freie Universität Berlin)

---