'Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient'

by Samuel Krug

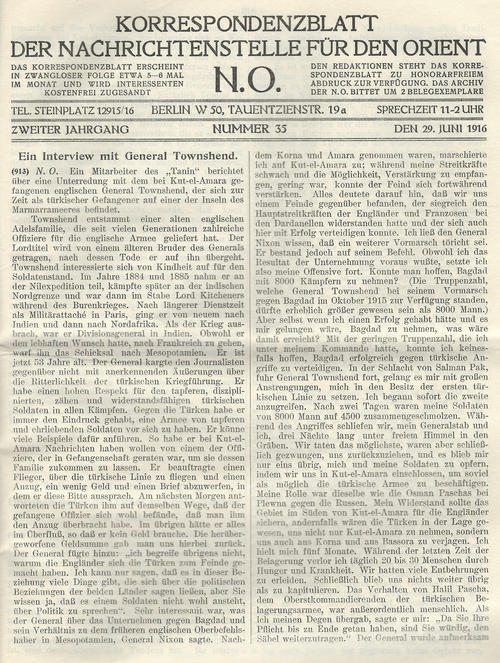

Newspaper edited by the 'Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient'

Image Credit: Personal collection, Photo: Oliver Stein

Shortly after World War One broke out, the German Foreign Office founded the propaganda organization “Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient” (NfO). The first director of the NfO was the German diplomat Max von Oppenheim (1860-1946), who wrote a memorandum in the fall of 1914. He brought forward a detailed plan for the insurrection of the Middle East and North Africa. The role of this memorandum and von Oppenheim himself is highly debated: while some regard him as the most influential actor in the German policy towards the Middle East, with close contact to Wilhelm II, others question this view and emphasize von Oppenheim’s limited access to policy-makers in general.

However, the organization he founded became one of the most active in the field of revolutionizing the “Orient” during the war. One of the main goals was to “revolutionize”Muslims worldwide, especially the colonial subjects of France, Russia and the United Kingdom, and thereby divert the Triple Entente’s military forces from European battlegrounds. For this purpose, the NfO produced vast literature ranging from shorter fliers to longer brochures and books. The texts were published in European and non-European languages, e.g. Arabic, Persian, Russian and Hindi. Recurring topics were questions on the legitimacy of colonialism, the importance of jihad and the disrespect towards Islam by the British, French and Russians. Examples for fliers are: Le droit de peuple géorgien, Le djéhad et le rôle de l’armée noire and British Rule in India. The attempt to alienate Muslims from the Triple Entente and to win them over for the German cause led to a special treatment of Muslim prisoners of war (POW). The NfO was involved in propaganda among the POWs at two camps for non-European prisoners (Zossen and Wünsdorf). The organization distributed a newspaper with the characteristic title al-Gihad, which appeared in different languages. The intention was to keep up the prisoner’s moral and inform them about current war events in a way that presented the German ambitions und activities in a favorable light.

Aims and Tasks

Another aim of the NfO was to (trans-) form the German public opinion on Islam and the Middle East. The two main reasons were the discontent of members of the German parliament and the public with the cooperation with the Ottoman Empire as well as fears of a Muslim upheaval in German colonies. Despite what has been called “Türkenfieber” by the contemporary Carl Heinrich Becker (1876-1933), which implies a craze for everything Turkish, i.e. “oriental”, the image of Islam and the Middle East had been rather negative. The NfO approached its task by circulating positive articles about Islam and the “Orient” in daily newspapers such as Vossische Zeitung, Berliner Tageblatt and Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung. In addition, the NfO published its own newspaper Korrespondenzblatt, renamed in 1917 to Der Neue Orient. It appeared under this name until 1943. Furthermore, citizens from North Africa and the Middle East traveled around Germany, campaigning for the involvement of the Reich in the region. Especially Salih ash-Sharif at-Tunisi (1869-1920) and Abd al-Aziz Shawish (1876-1929) frequently gave lectures to the German public. The latter stayed in Berlin after the end of the war and came to be one of the most important publicizing Egyptian nationalists in Europe. However, the close ties of the NfO with Arab and Indian nationalists did not lead to a formal involvement in intelligence operations.

Structural Organization and Personnel

The NfO was established as a collegial body and was therefore less hierarchical than other ministerial offices. The directors managed it very differently, either as a scholarly institute or as a governmental agency. Different linguistic sections formed the institution; the Arabic Section was the biggest, with more than ten members. Its head was Eugen Mittwoch (1876-1942), a professor at the University of Berlin, who became the third director of the NfO in February 1916. Oskar Mann (1867-1915) directed the Persian Section until his death, whereupon Sebastian Beck (1878-1951) filled this position. The Turkish Section was led by Martin Hartmann (1851-1918), the Indian Section by Ferdinand Graetsch (1878-1953), the Chinese/East Asian Section by Herbert Mueller (1885-1966) and the Russian Section by Harald Cosack (1898-1960). Apart from Friedrich Graetsch, a missionary with practical experience in India, all department heads were active in academia (Philology or Oriental studies), either during their employment at the NfO or after the war. The other German employees came from different areas. Although some were academics, as Helmuth von Glasenapp (1891-1963), who edited the Newspaper al-Gihad, others worked in the field of journalism, like Max Rudolf Kaufmann (1886-1963) and Friedrich Perzynski (1877-1965), who edited Das Korrespondenzblatt/Der Neue Orient together with Mueller. Active and former diplomats were also employed. Karl Schabinger von Schowingen (1902-1969), who was the second director of the NfO starting in spring 1915, worked for the Arab Section together with Edgar Pröbster (1879-1942) and Curt Prüfer (1881-1859), both part of the German diplomatic corps.

While the German staff possessed good linguistic skills, the NfO also relied on the work of non-German employees. Native speakers worked for the respective sections and helped with translations into both their native and foreign languages. The Muslim employees produced propaganda texts, which were published after an evaluation and censorship by the German employees. Furthermore, religious scholars such as Alim Idris (1887-1945?) or Muhammad al-Khidr Husayin (1857-1944), who later became a Grand Imam of al-Azhar, worked as imams in the aforementioned detention camps. The “Oriental” personnel had different backgrounds: they were religious and/or political activists, deserters from Entente armies, like Rabah Bukabuya (born 1875), diplomats, such as Halil Halid (1869-1931), and journalists. The intentions for joining the NfO varied, but reducing the non-German staff’s role to mere translators and propagandists for the German cause would be too simple. The NfO could be viewed as a platform that was used by different actors to pursue their respective goals. The German leadership was well aware of this fact and therefore monitored the activities of its non-German staff, but was still unable to prevent unintended results. For example, the nationalist Lala Har Dayal (1884-1939), who had been active for the Indian Section, defected to the British and published his experiences in the book Forty-Four Months in Germany and Turkey (1920).

Apart from the official staff, the NfO had several “corresponding members”. Again, they came from different fields, although Orientalists such as Enno Littmann (1875-1958) and Carl Heinrich Becker played the biggest roles. These members handed in articles, helped with translations and gave the NfO access to other platforms for expressing its views.

Network

Through its corresponding members and the official personnel, the NfO was intertwined with different governmental and non-governmental organizations. Aside from the involvement with the Foreign Office, which partially financed the activities of the NfO, the organization also had to consult the General Staff in questions of censorship and publication. For example, the office of Rudolf Nadolny (1873-1953), head of the General Staff’s political department, revised every issue of al-Gihad. Furthermore, the NfO was in close contact with embassies and consulates located in North Africa and the Middle East. In addition, the NfO secured the flow of information by opening branches in other locations, such as Tiflis, over the course of the war.

In terms of academic connections, the NfO had close ties with the “School of Oriental Languages” (Seminar für orientalische Sprachen) in Berlin. This facility, which was part of the University of Berlin, trained and prepared German colonial and diplomatic officials. Its professors and lecturers were Orientalists with a focus on the contemporary world and therefore were the ideal employees for the NfO. By including academics form different universities within the empire, from Hamburg to Frankfurt, the organization guaranteed that Orientalist competence would be at disposal if needed. On the other hand, this was another way of disseminating its ideas, as the teachers would spread the NfO’s views amongst their students or the German public.

The latter was one of the reasons for the cooperation with some of the many private associations that dealt with the “Orient”. An example is the “German Society for Islamic Studies” (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Islamkunde), which was founded by Martin Hartmann in 1912. Its aim to form the German public opinion on Islam was so close to the NfO’s task that there were recurring suggestions to merge the two organizations, which was ultimately never realized. Nonetheless themes and staff overlaps were not uncommon. The journalist Max Kaufmann was not only involved with the NfO, but was a member of the “German-Turkish Association” (Deutsch-Türkische Vereinigung) and worked for the newspaper Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung.

Conclusion

After the end of the war in November 1918, the NfO was renamed “Deutsches Orient Institut” (DOI). The new name was chosen to cover up the organizations involvement in propaganda. Still, one aim of the DOI was to strengthen the German-Middle Eastern “friendship”. Hartmann’s and Mittwoch’s vision for the DOI was to transform it into an educational institution, comparable to the “Seminar für Orientalische Sprachen” or the “Hamburger Kolonialinstitut”. After 1920, however, the traces of NfO and DOI taper off in public and archival sources.

No doubt, the success of the NfO in revolutionizing the “Orient” and spreading the jihad concept among Muslims was rather limited. A lack of funds and manpower, as well as internal conflicts, hindered the NfO in fulfilling this task. Schabinger von Schowingen and von Glasenapp give a vivid account of these struggles, especially of the interpersonal tensions, in their memoirs. However, the activities and publications of the NfO affected other fields. Firstly, the organization introduced Islam as a possibly important political factor to the German public. Secondly, the NfO became an intellectual meeting point for contemporary Orientalists and promoted careers of young scholars. Finally, and maybe most importantly, the NfO gave a voice to politically engaged Orientalists and consequently helped to politicize Oriental and Islamic studies.

Bibliography

- Bragulla, Maren, Die Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient. Fallstudie einer Propagandainstitution im Ersten Weltkrieg, Saarbrücken 2007.

- Hagen, Gottfried, German Heralds of Holy War. Orientalists and Applied Oriental Studies, in: Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 24/2 (2004), pp. 145–162.

- Hanisch, Marc, Max Freiherr von Oppenheim und die Revolutionierung der islamischen Welt als anti-imperiale Befreiung von oben, in: Wilfried Loth, Marc Hanisch (eds.), Erster Weltkrieg und Dschihad. Die Deutschen und die Revolutionierung des Orients, Munich 2014, pp. 13–38.

- Höpp, Gerhard, Muslime in der Mark. Als Kriegsgefangene und Internierte in Wünsdorf und Zossen 1914-1924, Berlin 1997.

- Kloosterhuis, Jürgen, "Friedliche Imperialisten". Deutsche Auslandsvereine und auswärtige Kulturpolitik, 1906-1918, Frankfurt a.M., Berlin 1994.

- Kröger, Martin, Revolution als Programm. Ziele und Realität deutscher Orientpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Wolfgang Michalka (ed.), Der Erste Weltkrieg. Wirkung, Wahrnehmung, Analyse, Munich, Zürich 1994, pp. 366–391.

- Lüdke, Tilman, Jihad made in Germany. Ottoman and German Propaganda and Intelligence Operations in the First World War, Münster 2005.

- Müller, Herbert Landolin, Islam, gihad ("Heiliger Krieg") und Deutsches Reich. Ein Nachspiel zur wilhelminischen Weltpolitik im Maghreb 1914–1918, Frankfurt am Main et al. 1991.

- Schwanitz, Wolfgang G., Max von Oppenheim und der Heilige Krieg. Zwei Gedenkschriften zur Revolutionierung islamischer Gebiete 1914 und 1940, in: Sozial.Geschichte, Neue Folge 19/3 (2004), pp. 28–59.

- Will, Alexander, Kein Griff nach der Weltmacht. Geheime Dienste und Propaganda im deutsch-österreichisch-türkischen Bündnis 1914–1918, Cologne 2012.

Citation

Krug, Samuel: ‘Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient’ (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---

Samuel Krug, M.A. (Freie Universität Berlin)

Mr. Krug is a PhD candidate at the Freie Universität Berlin and works since 2015 on the 'Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient'.