German Soldiers in the Balkans, 1915-1918: Introductory Text

by Oliver Stein

Book cover from 1916, Arthur Dix (1875-1935) (detail)

Image Credit: personal collection, photo: Oliver Stein

This section of the exhibition is about western soldier’s encounter with a region that, while lying within Europe, was regarded as an intersection between the Orient and the Occident. During the First World War, many nationalities including Germans, Britons and Frenchmen reached the Balkans. The following will cover German soldier’s contact with the Bulgarian allies and the Balkan peoples in the occupied areas.

The Balkans as a crisis region

As early as the 19th century, the diverging interests of the Great Powers as well as the local ethnic conflicts made the Balkans a region that echoed international crises and that provoked the threat of war. The First Balkan War of 1912/13 exemplifies a previous climax in this unrest, which had brought Europe to the brink of a great war. These events received great attention among the German public. However, the Balkan League split in two during the conflict over the conquered Ottoman areas and Bulgaria was defeated by their former allies in the Second Balkan War. Through these events, the nationalistic trenches between Balkan citizens were further deepened.

Alliances and the course of First World War in the Balkans

If the European powers had exercised a different crisis diplomacy, the shots in Sarajevo could have led merely to a Third Balkan War between Austria-Hungary and Serbia instead of providing the trigger for the First World War. At first, only Serbia and Montenegro of the Balkan states were at war - the others declared their neutrality. However the Entente and the Central Powers courted the other countries in southeastern Europe. In September 1915, Germany and Austria-Hungary succeeded in inducing Bulgaria to enter the war by promising territorial gains in Serbia and Macedonia. In one of the ensuing mutually offensives, the Allies succeeded in occupying Serbia until the year’s end. Meanwhile, the Entente looked to come to Serbia’s aide and, against the wishes of the Greek king, landed among the troops under French leadership in Salonica. Consequently, beginning in 1915, a further front line emerged: the Salonica front in Macedonia. Up to a million soldiers from nearly all of the Entente coalition countries were sent to this front to face the Bulgarian-German troops in the trenches. Rumania, neutral until this point, joined the Entente forces in August 1916 and began an offensive in Austrian-Hungarian Transylvania. The Romanians, however, could hardly hold their own against the Central Powers’ following counter-offensive and by the year’s end the majority of the country was occupied. The Romanian army had pulled back to the Siret River where positional warfare continued until November 1917.

The happenings over the course of the First World War in the Balkans were distinguished by mobile warfare in the campaigns against Serbia and Romania, as well as by trench warfare that characterized the combat in Macedonia and intermittently the combat on the Siret. As the fronts of the Central Powers had already begun to falter towards the end of the war, the large-scale French-British offensive in Macedonia in September 1918 led to Bulgaria’s collapse and the war’s conclusion in the Balkans.

The German-Bulgarian brotherhood in arms

For both sides, especially in the Balkan theater of war, the First World War clearly adopted the character of a widespread coalition war. In their combat together, the Germans, Austrian-Hungarians, Bulgarians and Turks not only opposed Serbians and Romanians, but also an army composed of the British, the French, Australians, Italians, Russians and Greeks as well as colonial soldiers from Indochina and Africa. Similar to the Entente side, the Central Powers’ alliance was equally characterized by successful cooperation as by continuing conflict. With an increasing duration of war, however, the alliance became more fragile so that the sworn union, displayed for instance on propaganda postcards, was further challenged by oppositional war objectives.

Many German soldiers reached the Balkans within the framework of the Serbian and Romanian campaigns, each campaign having an army of more than 50,000 men. Additionally, German soldiers were active in fluctuating numbers on the Macedonian front, in Serbian and Romanian occupied areas, and in Bulgaria until the end of the war. These men were lodged either in encampments with barracks or tents, as can be seen in the photographs from Macedonia, or alternatively were billeted with the civilian population in villages and cities. There they often encountered natives and Bulgarian soldiers. The personal testimonies passed down from these soldiers speak of a good camaraderie with the allies and a good relationship with the population, but also of the differences in mentality and military culture. Men often complained that the Bulgarian military was inefficient and too sensitive to criticism. The Bulgarians, on the other hand, often found the Germans to be arrogant and domineering. The German-Bulgarian cooperation on the front, like in the occupied areas, was regularly accompanied by conflict that was not only based on the divergent war objectives and interests, but also on the cultural differences and misunderstandings.

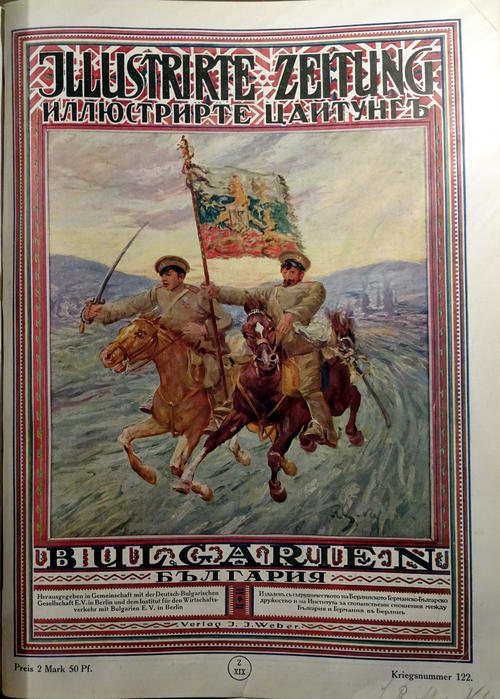

Cover of 'Illustrirte Zeitung, 30. November 1916, Special Edition Bulgaria

Image Credit: personal collection, photo:Oliver Stein

Collective celebrations and convivial events served among other purposes to deepen the bond between the brothers in arms. Images from the communal sporting events and from the preparation for a German-Bulgarian victory celebration in Nish in January 1916, in which the Tsar Ferdinand and Kaiser Wilhelm II also took part, attest to this. In Germany itself, an intense propagandistic operation was set in motion to deepen the alliance. Future German economic interests in the Balkans also stood behind these efforts, which operated under the name “Central Europe” (Mitteleuropa) and which had a common trading zone in Bulgaria in mind for the Central Powers. In November 1916 a special edition of Leipzig’s renowned ‘Illustrirte Zeitung’ was published in both the German and Bulgarian language. In the German press, the term “Prussians of the Balkans” for the Bulgarians became a popular appellation. This label was supposed to value the Bulgarians’ discipline and will to modernize, while also suggesting a desired political closeness with the allied partner. However, even the picture on the title page of the ‘Illustrirte Zeitung,’ rendering Bulgarian cavalrymen atop small Bulgarian horses and clothed in uniforms similar to those of the Russians, unintentionally shows a visible external disparity from the German “Self”.

Many of the German soldiers deployed to the Balkans, then, were in the position to deny this internal similarity between the Bulgarians and the Germans expressed through “Prussians of the Balkans” - the apparent differences were all too obvious to them in their daily military collaboration. This evaluation was influenced not only by the limited military effectiveness of the allies, but also by the perception of violence, among other things, in the Balkans. In Serbia and Romania German soldiers were continuously witness to war atrocities inflicted on the civilian population and prisoners of war. ‘Ethnic cleansing’, especially in Macedonia, stood on the agenda. Corresponding perceptions of the unbounded violence, which the German soldiers could have also ultimately witnessed within the Austrian-Hungarian occupation regime, strengthened their stereotype of the wild and uncivilized Balkans.

Perception of the Balkans as the ‘Orient’

The German soldiers’ perception of the Balkans was dominated by the feeling of unfamiliarity and, not infrequently, by the latter’s’ inferiority. To the Germans in the area, the Balkans usually was regarded as belonging to the ‘Orient’. The significant percentage of Muslims among the population, especially in Macedonia, was one reason for this assessment. Veiled women, tea drinking Turks and mosques were beloved photo motifs; they appeared more exotic than the similarly eye-catching and colorful costumes of the Christian demographic groups. To the great displeasure of the Bulgarians, who had worked for years on the westernization and modernization of their land, German illustrators favored the minarets or other oriental references in their scenery when creating advertisements related to Bulgaria. Additionally a great deal of poverty and backwardness caught the soldiers’ attention in the Balkans: gypsies and beggars as well as old-fashioned methods for agriculture like ox carts and wooden ploughs, were especially likely to be photographed and often described as being ‘old testament-like’ or ‘archaic’.

Transportation conditions and topography

The transportation conditions in the Balkans were also perceived as being backwards and, like on the Eastern front, similarly posed a great challenge to the German military. There were only a few railways. The most important connection was the Balkans Express that, since the victory over Serbia, again traveled from Berlin through Vienna, Belgrade and Sofia to Constantinople. The railway also stood as the central supplies and transport line in the Balkans and Ottoman Empire. Additionally, transport convoys with motor trucks came to carry great importance. German and Bulgarian sappers, however, had to first build the roads through mountainous Macedonia, on which these transport convoys could later drive. In the fall, many of the roads proved to be impassable for automobiles, which posed a particularly serious problem in the campaigns against Serbia and Romania. However it was the ox-drawn carts of the Bulgarians, previously so ridiculed by the Germans, that stood the test against the muddy roads.

The soldiers in the Balkans had to acclimate to a generally harsher climate, in which hot summers alternated with the cold winters. In 1916 a khaki-colored tropical uniform was introduced for the troops in Macedonia that drew on the equipment from the German expedition in China. The unaccustomed climate also expedited the spread of diseases, which led to great losses on both sides of the front line in Macedonia.

Memory

As on all fronts, the German soldiers in the Balkans made use of their service to procure and collect souvenirs. To this end, keepsakes were manufactured like, for example, the small enamel pin with the Bulgarian emblem shown here. Soldiers’ war badges belonged to the great amount of war memorabilia produced during the war that served to popularize the alliance with the Bulgarians and other alliance partners among the population. The deployed German soldiers, however, also made sure to erect monuments to their presence in Bulgaria: thus one photograph captures the moment in which the members of the 3rd Company of the 21st Infantry Regiment, stationed in the barracks in Bulgarian Varna, erected a monument to their unity during the war. One of the particular forms of remembrance is the Vivat Ribbon, which was issued on the occasion of a military victory and was worn on clothing or collected. The Vivat ribbon shown here remembers the victory of Tutrakan in 1916 whereby Bulgarian troops, with German participation, took a Romanian stronghold.

After the war, the vows of friendship and brotherhood in arms faded. The German and Bulgarian memoirs debate over an assessment of the victory of Tutrakan - each side claiming the greater hand in the success. In the mid 1930’s, as Bulgaria and the German Reich neared a political and economical rapprochement, the time of the mutual alliance was called back to mind. This was especially the case for the years of the Second World War, when Bulgaria and Germany once again stood in a war alliance. The Bulgarian war ministry began with the issuance of remembrance medallions to those former world war participants who had served in the Balkans.

Bibliography

- Am Rande Europas? Der Balkan - Raum und Bevölkerung als Wirkungsfelder militärischer Gewalt, hrsg. von Bernhard Chiari und Gerhard P. Groß, München 2009.

- Crampton, R. J.: Bulgaria (=Oxford History of modern Europe), Oxford 2007.

- Der unbekannte Verbündete. Bulgarien im Ersten Weltkrieg, hrsg. vom Heeresgeschichtlichen Museum, Wien 2009.

- Der Erste Weltkrieg auf dem Balkan, hrsg. von Jürgen Angelow unter Mitarbeit von Gundula Gahlen und Oliver Stein, Berlin 2011.

- Gahlen, Gundula: Erfahrungshorizonte deutscher Soldaten im Rumänienfeldzug 1916/17, in: Am Rande Europas? Der Balkan - Raum und Bevölkerung als Wirkungsfelder militärischer Gewalt, hrsg. von Bernhard Chiari und Gerhard P. Groß, München 2009, pp. 137-158.

- Mayerhofer, Lisa: Zwischen Freund und Feind. Deutsche Besatzung in Rumänien 1916-1918, München 2010.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Serbia's Great War, 1914-1918, West Lafayette 2007.

- Stein, Oliver: Die deutsch-bulgarischen Beziehungen seit 1878, in: Zeitschrift für Balkanologie 47 (2011), No. 2, pp. 218-240.

- Petrova, Deniza: Der Rumänienfeldzug 1916/17 in der bulgarischen Kriegserinnerungskultur, in: Der Erste Weltkrieg auf dem Balkan, Berlin 2011, pp. 257-269.

- Stein, Oliver: „Wer das nicht mitgemacht hat, glaubt es nicht.“ Erfahrungen deutscher Offiziere mit den bulgarischen Verbündeten 1915-1918, in: Der Erste Weltkrieg auf dem Balkan, hrsg. von Jürgen Angelow unter Mitarbeit von Gundula Gahlen und Oliver Stein, Berlin 2011, pp. 271-287.

- Stein, Oliver: Zwischen Orient, Rußland und Europa. Zum Bild der Bulgaren und ihres Militärs in der deutschen Presse 1912-1918, in: Am Rande Europas? Der Balkan - Raum und Bevölkerung als Wirkungsfelder militärischer Gewalt, hrsg. von Bernhard Chiari und Gerhard P. Groß, München 2009, pp. 159-175.

- Torrey, Glenn E.: The Romanian battlefront in World War I, Kansas 2011.

Citation

Stein, Oliver: German Soldiers in the Balkans, 1915-1918. Introductory Text to the Exhibition of www.mwme.eu (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---

Translated by Westrey Page (Freie Universität Berlin)

---