French Soldiers’ Gaze upon Italian and Egyptian Women: Gender, Masculinity and Sexuality in Militarised Cultural Encounters.

by Fergus Robson

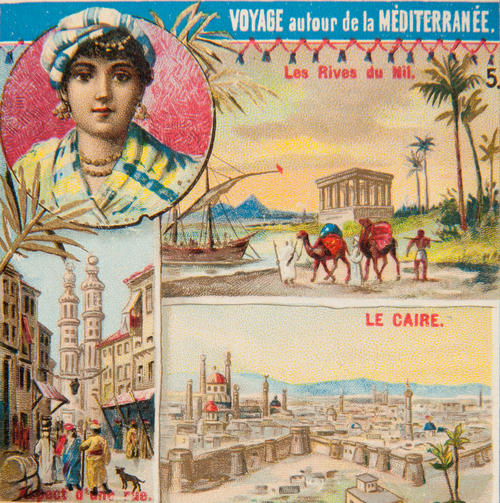

Voyage autour de la Méditerranée V; Égypte (detail)

Image Credit: © MuCEM, Marseille,France, Marseille/RMN-Grand Palais

The way soldiers interact with and treat women has been problematic for probably as long as soldiers have existed. While the previous post introduced the ‘tourist gaze’, where women are concerned this interacts with the ‘male gaze’. The intersection of the two is a powerful means of defining, categorising and exerting control over women. This discussion will not avoid sexual violence and coercion which are seemingly inseparable from warfare, it will however focus on the discursive and definitional aspects of encounters between French soldiers and the female populations of countries they travelled through or occupied. The analysis will go beyond strictly male-female encounters, encompassing cultures of masculinity and understandings and portrayals of gender and sexuality in other cultures. These illustrate the cultural norms that determined the way French men thought and wrote about women and their place in society, which I hope will illuminate the distinctive characteristics of French perceptions of gender in the late 18th century.

It is important to note the drawbacks to using memoirs and letters to analyse the way these soldiers actually acted. Whether writing for posterity, or to family members, it is likely that our authors glossed over their own or their comrades’ reprehensible behaviour. For this reason questions of rape and sexual violence will feature less prominently in this discussion than the ways in which French soldiers constructed images of French femininity and the place of women in society, in opposition to what they saw in Italy and Egypt. Their view of Italian and Egyptian masculinity and sexual mores, in distinction to French, will also receive attention. These are moreover fruitful avenues of inquiry into the construction and transmission of ideas of national identity as elaborated through gender and sexuality.

Preliminary Patterns and Significant Divergences

Carte Réclame; Le Carnaval en Italie; Pulcinelluzza

Image Credit: © MuCEM, Marseille, France, Marseille/RMN-Grand Palais

The first aspect that must be noted is that the ways in which the French soldiers being studied wrote about women were very different in both countries. The visual impact of women clad in the Burkha and the exposure to received versions of Islamic domestic practises; from female seclusion to the harems of the Mamelukes, not to mention the existence of eunuchs, all meant that their experience in Egypt was considerably more jarring and gave rise to a more thorough ‘othering’, than in Italy. A theme common to both was the perceived lack of sexual modesty in contrast to French women. This tendency to valorise French womanhood (in and on male terms), for its decorum, reserve, modesty and beauty, can be observed in many cultures as they seek to assert their superiority over an ‘other’. A not unexpected aspect of French soldiers’ gender imaginary was their self-characterisation as braver, more honourable and more courteous than the Italian or Egyptian men they encountered. While this took different forms in both countries it nonetheless constitutes a common theme.

Femininity: Foreign and French

While campaigning far from France the soldiers studied tended to idealise their fatherland, including French women. Their disillusionment was often stark when they returned home but the ways in which they wrote about foreign women can tell us a lot about how they envisaged the idealised française. A frequent invocation was their beauty and elegance compared to those of Italy and Egypt; sometimes expressed as disgust with the appearance of the locals. The anonymous dragoon described Egyptian women as ‘small, thin and hideous’, Rougelin called them disgusting, and the future general Pépin maintained that had he stayed 50 years in Egypt he would still detest the faces of local women. Bricard and Laval both noted the local predilection for dark mascara, which they ridiculed. Almost all of the soldiers commented on Egyptian women’s dress, some merely noted the veil, whereas others went into greater depth, usually to condemn and/or belittle local mores. Ladrix for instance noted the ‘importance they attach to covering their faces yet their robes allow the rest of their bodies to be seen’, Joseph Moiret and Pierre Millet agreed, which probably says more about soldiers’ prying eyes than local immodesty. Vaxelaire, Bricard and Millet all claimed that Muslim women’s dress, dance and sexuality were ‘indecent’, ‘filthy’ and ‘unspeakable’, from which we might surmise either a certain religiously informed prudishness or resentment at having been aroused by women they would rather have been adverse to. Moiret, Bricard, the militaire and the dragoon maintained that in the countryside women and children often went completely naked, a claim which would tend to valorise the implicitly more civilised French peasantry. Ladrix and Bricard also noted the much finer, even luxurious clothing of wealthier women but put it down to their being the slaves of their wealthy husbands who had them decoratively adorned for their own pleasure. Not all the French soldiers in Egypt were so repressed or so racist. Tales of officers taking Egyptian mistresses, and even wives abounded, while Moiret agonised over the whether the beauty of Zulima was worth converting to Islam. Thurman described the women of Rosetta as ‘gracious and animated’, and Laval noted their vigour and fertility.

Italian women fared somewhat better among our memoirists, Bricard praised them as ‘very likeable and yielding but also greedy and nonchalant, overall charming women in the bedroom but not for marriage’. Putigny, in Milan, described the ‘graceful movements of the easy-going, dark women’ who he referred to as the délices of Milan. Lecoq was also a fan of Milanese ladies, who he described as ‘youthful, beautiful and good’. Legrot encountered ‘quite a pretty girl, despite being dark, like all the women of the Piedmontese countryside’. This aesthetic preference for European women, more similar to those they were familiar with is maybe not surprising, and the yearning for familiarity is underlined by the allusion to the darker skin of Italian women, who were nonetheless still preferable to Egyptian. Reinforcing this point was Moiret’s praise for Zulima’s pale skin.

Throughout all of these discourses however is the underlying implication that French women were more beautiful, more modest, more civilised and were treated better than women they encountered in Egypt but also in Italy. This idealised image of French femininity, while complimentary in a sense, was constructed rather than real and served as much as a means of controlling French women as it did denigrating foreign. Perhaps the most honest in this regard was Vaxelaire who maintained that ‘dancing after church was practised everywhere in Europe and could lead to debauchery and perdition’, although he still claimed that ‘Muslim dance is so indecent that modesty prevented him from discussing it’.

Women and their Place(s) in Different Cultural Worlds

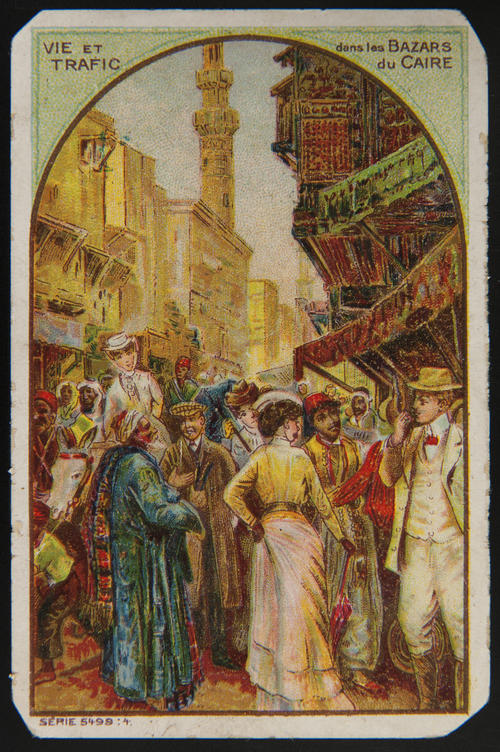

Vie et Trafic dans les Bazars du Caire

Image Credit: © MuCEM, Marseille, France, Marseille/RMN-Grand Palais

Similar patterns of valorising the social and cultural roles and virtues of French women can be detected when the memoirists wrote about work, family life, and society. When thinking about how soldiers’ perceived such things two differences in their experiences are important to note. In Italy they were often billeted on families whereas this did not happen in Egypt and Italian women’s social roles, while not identical to those in France, were much more familiar than those prevalent in Egypt. Hence their opinions on Egyptian women’s lives were less well informed and tended to exaggerate and rely on hearsay, which conversely makes them an excellent source of detail on how French men imagined ideal feminine roles.

Godet’s praise for the simplicity and industriousness of Puglian noble women, who unlike French or Northern Italians, worked in their own kitchens. As we will see below, any French soldiers told stories about saving women from brutal attack, reinforcing their own virtue as honourable men and soldiers. They also however reported a number of inverse instances when women saved French soldiers’ lives. During the evacuation of Italy, Bricard and a companion were saved by a ‘pretty young lady at the crossroads’, who fed and hid them from rampaging vengeful peasants. Chatton, left behind when the army moved out of Benevento in Campania, was saved by local women when they heard him cry out for God’s mercy upon being captured, refusing to let their husbands kill a ‘good Christian’. This was not a uniquely European trait however, Bricard reported that a soldier in Damanhour was saved by an old woman who hid him during the insurrection against the French there. These instances demonstrate the prevalence of images of women as more caring and merciful, less violent or willing to countenance murder. The potency of such imagery merely rendered women who abandoned these roles all the more monstrous, as in Chatton’s description of the ‘ferocious face’ of a woman brandishing an axe in Benevento.

The thought of women not attending church seems to have shocked many soldiers, even after years of Revolution and the army’s secular reputation. Cailleux maintained that since ‘women are not allowed in Mosques, they have no religion’, Bonnefons pitied them for being ‘denied the consolation of religion, especially regarding the miserable state of slavery to which they are reduced’. Also very jarring for French soldiers was the sight of women engaged in masculine pastimes such as smoking tobacco, drinking or frequenting bars as Laugier encountered in the Tyrol. Putigny remarked on Dutch women’s ‘mania for smoking pipes’ and Bonnefons claimed that it was a common sight in Egypt. These examples illustrate that French women place was largely domestic, that they should be gentle, merciful, pious, and should not infringe upon masculine spaces or pastimes.

Masculinity and Sexuality.

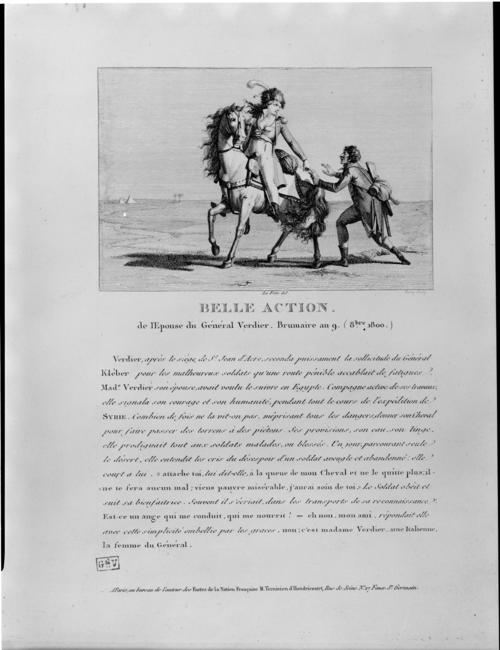

Belle Action de l’épouse du Général Verdier. Brumaire an 9 (octobre 1800)

Image Credit: © Musée de l’Armée/RMN-Grand Palais, Paris, France/Pascal Segrette

The military and gender relations are both potent crucibles in which images of manhood were constructed, all the more so when they intersected. Most memoirists strongly denounced pillagers and rapists in the army and a few demonstrated their masculine virtue by saving damsels in distress. The cultural difference is evident when Legrot at least feigned offence that Italian women would always try to pay for any good deed rendered; one whom he saved from rape at the hands of ‘two monsters wearing the same uniform as I’, insisted on rewarding him with two sausages, while later, having intervened in a bar room brawl and saved the innkeeper, he declined her offer of gold, instead asking her to pray for him. This meant that for him French men were truly gallant whereas it is implied that Italian men would expect recompense in similar situations.

Gallantry also applied to seduction, Moiret’s dalliance with Zulima is framed as a model of respectful and courteous but restrained flirtation. In a similar sense, Duviquet’s seduction of the beautiful young wife of a wealthy merchant Lyon draws on imagery soldiers’ prowess as conquerors in the bedroom as well as on the battlefield. Laugier, whose self-regard was enormous, portrayed himself as eminently desirable but honourably chaste, writing that ‘I discerned an adoring gaze in the eyes of my host’s daughter’, he declined her ‘honest love’ because of his strong sense of duty. Here we see a variety of visions of French manhood laid bare in a soldier’s ego. The allure of French soldiers was supposedly so great that women who had become pregnant during their passing ‘enquired affectionately for their former lodgers’ according to Bricard, and elsewhere he reported local women’s tears upon the departure of the French. Such versions of romantic and sexual encounters tell us much more about how French men liked to see themselves than the realities of gender relations during warfare.

Another way in which we can use soldiers’ memoirs to elaborate an idea of how they saw themselves sexually is by juxtaposition to the way they represented gender relations in Egypt. Nearly all insisted that Muslim women were the slaves of their husbands who, in a classically orientalist mould, were debauched and in Bricard’s words ‘subjected their wives to their caprices and fantasies’ or according to Moiret’s self-justificatory account, ‘only wanted fat masses of flesh...upon whom they imposed practises contrary to nature, neglecting legitimate pleasures’, Millet agreed, stating that ‘they are all sodomists and keep young men and women against whom they commit atrocious crimes’, while Cailleux maintained that all ‘Turks saw women as creatures sent to earth by Muhammad solely for men’s pleasure’. This set of highly prejudiced imagery underlines two important points which these French soldiers evidently felt characterised them; they were gallant and courteous towards women and they would never engage in libertine sexual pursuits like sodomy. This imagery serves to reinforce their self- perception as a race with fine taste, restraint and virtuous sexual mores, who moreover were respectful of women.

Bibliography

- J. Barada, (ed.) ‘Lettres d’Alexandre Ladrix, Volontaire de l’an II’ in Carnet de la Sabretache, vol. 29, no. 303 (1926)

- P. Belfond, ed. Mémoires sur l’Expédition d’Égypte: Joseph-Marie Moiret Capitaine dans la 75e demi-brigade de ligne (Paris, 1984)

- P.-L. Cailleux, ‘Campagne d’Égypte et de Syrie (extrait du cahier de Pierre Louis Cailleux, caporal dans le 2e légère) in Carnet de la Sabretache (1931, 1932)

- H. Gauthier-Villars, ed. Mémoires d’un vétéran de l’ancienne armée (1791-1800) siège de Mayence, pacification de la Vendée, campagne d’Égypte (Paris, 1900)

- E. Gridel, Capitaine Richard, eds. Cahiers de Vieux Soldats de la Révolution et de l’Empire, (Paris, 1903)

- L. Larchey, ed. Journal du canonnier Bricard 1792-1802, publié pour la première fois par ses petit-fils Alfred et Jules Bricard (Paris, 1891)

- ‘Lecoq, journal d’un grenadier de la Garde’ in La Revue de Paris, vol. 18, no. 5, 17, (1911)

- F. Masson, ed. Souvenirs de Maurice Duviquet (de Clamecy) Vendée, armée de réserve, la Westphalie sous Jérôme-Napoléon (1773-1815) (Paris, 1905)

- Cmdt. Merreau, (ed.) Journal d’un dragon d’Égypte (14e dragons) (Paris, 1899)

- S. Millet, ed. Le Chasseur Pierre Millet, Souvenirs de la Campagne d’Égypte 1798-1801 avec introduction, notes et appendices (Paris, 1903)

- L. G. Pélissier, (ed.) De la guerre et de l’anarchie: les cahiers du capitaine Laugier ou Mémoires historiques des campagnes et aventures d’un capitaine du 27e régiment d’infanterie légère, par Jérôme-Roland Laugier (Aix-en-Provence, 1893)

- L.-G. Pélissier, ed. Un soldat d’Italie et d’Égypte (souvenirs d’Antoine Bonnefons, 7 novembre 1792 – 21 février 1801) in Carnet de la Sabretache series 2, vol. 1, no. 121, (February 1903)

- N. de Puitspelu, ed. Mémoires des soldats: Les trente années de service du capitaine Legrot (Nyons, 1891)

- B. Putigny, (ed.) Le Grognard Putigny; Baron d’Empire (Paris, 1980)

- Louis-George-Ignace Thurman, Bonaparte en Égypte, souvenirs publiés avec préface et appendices par le comte Fleury (Paris, 1902)

- G. Wiet, (ed.) ‘Journal du lieutenant Laval; mémoire inédit sur l’expédition d’Égypte’ in Le Revue du Caire no. 29, April 1941

See also

- M. Agulhon, Marianne into battle: Republican imagery and symbolism in France, 1789- 1880 (trans. J. Lloyd, Cambridge, 1981)

- M. Broers, The Napoleonic Empire in Italy, 1796-1814: Cultural imperialism in a European context? (Basingstoke, 2005)

- J. Cole, Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle-East (Basingstoke, 2007)

- A. Forrest, Napoleon's men; the soldiers of the Revolution and Empire (London, 2002)

- J. Urry and J. Larsen, The tourist gaze 3.0 (New York, 2011)

- S. Woolf, 'French civilization and ethnicity in the Napoleonic Empire' in Past and Present no. 124, (1989)

Citation

Robson, Fergus: French Soldiers’ Gaze upon Italian and Egyptian Women: Gender, Masculinity and Sexuality in Militarised Cultural Encounters (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---