French Soldiers encounter European and Arabic Architecture.

by Fergus Robson

Palace of the Senate in Rome, the Tibre (early 19th Century)

Image Credit: © MuCEM, Marseille, France/RMN-Grand Palais/Jean-Gilles Berizzi

Architecture, from the symbolism of vast palaces, sites of power and places of culture, to the layout of city streets and the construction of the dwellings of the poor, both urban and rural, constitutes one of the first omnipresent sights of difference when we arrive in a new country. Sometimes this difference is pronounced, sometimes it is subtle, in today’s world a degree of architectural homogenisation is breaking down older stylistic differences. Most of the soldiers whose writings we are using had in many cases barely left their own region prior to enlisting or being conscripted. This meant that, when they encountered the building styles typical of other regions of France through which they passed, their first impression was an accentuation of their difference from other French. Environmentally informed regional gradation in architectural styles meant that they would have seen similarities and differences in the buildings they saw. This gradation also meant that the architectural style of Mediterranean France and adjacent areas of Italy, would have had more in common with each other than with the buildings soldiers from Normandy or Alsace were familiar with. In this sense exposure to changing architectural styles did not immediately enhance a particular sense of French specificity but rather informed an evolving awareness of cultural difference and similarity.

Why Architecture?

Charles Louis Fleury Panckoucke, Frontispiece pour La Description de l’Égypte (1824)

Image Credit: © Musée de l’Armée, Paris, France/RMN-Grand Palais/Emilie Cambrier

Massacre des Mameluks Rebelles dans le Château du Caire (25 avril 1800)

Image Credit: © Musée de l’Armée, Paris, France/RMN-Grand Palais

This is why architecture is an ideal theme with which to begin this blog, it was not experienced as a monolith, some soldiers were more or less conscious of it. Captain Thurman*, commented frequently while others rarely mentioned it or did so from different perspective to Thurman, the genial and sympathetic military engineer. Three overall themes however emerge from their recorded experiences: a ‘tourist gaze’, a pronounced sense of cultural difference and a more critical take on ‘inferior’ Italian or Egyptian construction. Where these themes intersect is particularly pertinent to the development of ideas of French and European architecture and hence, specificity and identity. A later post will deal with antiquities and monuments since these provide a rich seam of material and mentalities in themselves.

The 'Tourist Gaze"

The ‘tourist gaze’, is best characterised by soldiers like Antoine Bonnefons, who commented on the architecture, prominent buildings and cityscapes of the towns he passed through, while at the same time noting what he saw as the poorer construction and dilapidation of Egyptian towns. Many of the soldiers who fought in Italy greatly admired the grand civic, ecclesiastical and administrative buildings. Charvet for instance remarked upon the Duomo in Milan, the theatre we know as La Scala, as well as the “spaciousness and luxury of the buildings”. Others, in tune with their vocation, were more impressed by military fortifications, such as Bonnefons who frequently admired the “top-class citadels” he saw in Ceva and Tortona and the excellent barracks and military magazines in Coni. Others are carried away by the magnificence of city centres, as was Bricard in Brussels and Milan, both of which he felt rivalled Paris due to the elegance and richness of the architecture and shops. While the future baron Putigny, at the time a lieutenant, engaged with Venice much as a tourist would today, describing his “total relaxation as I drifted through the canals on a gondola, admiring the palaces and churches”. This tendency was much less pronounced in Egypt although Rosetta and Damietta on the delta coast inspired some admiration, Bonnefons decided that Rosetta was “the best built town with many beautiful buildings”. Thurman agreed that it contained elegant houses, while, in a recognisably touristic tone, he also praised a “beautiful mosque, surrounded by sycamores, on the banks of the Nile”. The soldiers were generally more impressed by the antiquities they encountered in Egypt, which they explored, measured and described in detail, but more shall be written about that in a future post.

Cultural Difference

George Cruikshank, Seizing the Italian relics (1814)

Image Credit: © Musée de l’Armée, Paris, France/RMN-Grand Palais

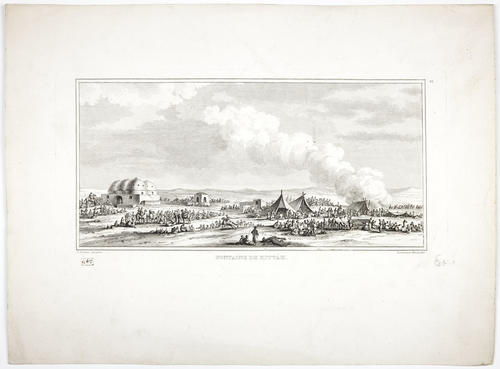

The sense of cultural difference experienced by French soldiers as they moved through different regions and countries was often pronounced, and not merely as difference between French and ‘others’. Captain Laugier observed that two neighbouring towns, Pontebba Veneta and Pontebba Austriaca, as their names imply, one in Venetian territory and the other in Austrian, were completely different. He listed a variety of cultural differences but architecturally he notes the prevalence of Italian style construction in Pontebba Veneta and the differently shaped chimneys. One of the most striking observations of cultural difference came from Bonnefons when he noted that in Malta “the houses were built and laid out in the Oriental manner”, in implicit opposition to the European style. The anonymous memoir of ‘A dragoon in Egypt’ contains a similar reference to Cairo, “an immense town...in which the houses are not laid out like those in Europe and take up more space”. Such observations illustrate the processes through which a sense of a European identity, as well as a French one, could slowly take shape through a multiplicity of sensory experiences.

French/European ‘Superiority’

This sense of cultural difference could be taken in a broadly tourist sense, but more often in Egypt at least it carried with it negative connotation of cultural superiority. Pierre Millet for instance noted that the size and population of Cairo were greater than any French city but that

“its streets are narrow, incommodious and there were no promenades”. Similar statements as to both the impressive size of the city as well as to the narrow, dusty, dirty streets, and the incessant boisterous street-life were repeated by most of the soldiers. Often these observations were accompanied with qualifications about the “now obscured splendour” (of Cairo) or that “Alexandria presented a mere shadow of its former glory”. Perhaps the most eloquent of these was Thurman’s “what a visual contrast between this African city and our European towns... Alexandria, once so powerful, now so decayed”. While for men who in many cases hailed from rural France, their attitude to villages and the peasantry often took on a similarly superior tone. In Malta, Bricard remarked upon how most were “no more than savages who lived in very rustic homes”, while in rural Egypt he claimed that “the inhabitants live like animals, most of their houses are underground”. Similarly, Bonnefons maintained that Qatyeh (Qatya) was no more than “a scattering of miserable huts” and the more sympathetic Thurman, while describing an “impoverished Arab village” tells us that “the houses were like all those inhabited by Fellahs; real pigeon huts”, elsewhere describing them as “disgusting cabins pulsating with vermin”.

Architecture, judgment and the colonial ‘self’ and ‘other’

Such judgments were bound up in the sense of national superiority and Oriental decline that informed and was used to justify future colonial endeavours. This is most starkly illustrated when they praise the Frankish quarters, of the Cairo, Alexandria and Rosetta, as the most attractive, cleanest, best built and best maintained. Thereby intimating the sort of attitude that would lead future generations of colonial invaders and administrators to justify their domination and attempted subjugation of foreign cultures, traditions and ways of life. Because whatever about the flashes of admiration for a beautiful mosque, a stunning ruin or impressive palaces, the implication of even the ‘tourist gaze’, especially when turned on Egypt, was that ‘this place, these people need us to bring prosperity, to restore their former glories and to drag them into the world as we see fit to shape it’. The world encountered by these French soldiers as they passed through Italy and Egypt became more and more alien the farther they went, reinforcing their sense, first of their regional, then of their French identity and by the time they had crossed the Mediterranean, their sense of what was European. These militarised cultural encounters, with buildings and places, but also the people, their languages, customs and ways of life, helped to develop and strengthen their sense of difference, identity and superiority.

Bibliography

- M. Agulhon, Marianne into battle: Republican imagery and symbolism in France, 1789- 1880 (trans. J. Lloyd, Cambridge, 1981)

- M. Broers, The Napoleonic Empire in Italy, 1796-1814: Cultural imperialism in a European context? (Basingstoke, 2005)

- J. Cole, Napoleon’s Egypt: Invading the Middle-East (Basingstoke, 2007)

- *A. Fierro, Bibliographie critique des Mémoires sur la Révolution écrits ou traduits en Francais (Paris, 1988) – Full references to all the soldiers’ mentioned in the post can be found in this work.

- A. Forrest, Napoleon's men; the soldiers of the Revolution and Empire (London, 2002)

- A. Forrest, K. Hagemann and J. Rendall, eds. Soldiers, citizens and civilians: experiences and perceptions of the revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, 1790-1820 (Basingstoke, 2009)

- A. Forrest, K. Hagemann, E. François, eds. War memories: The Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars in modern European culture (War Culture and Society, 1750-1850) (Basingstoke, 2013)

- M. Jasanoff, Edge of Empire: Conquest and collecting in the east, 1750-1850 (London, 2006)

- H. Laurens, L'Expédition d'Egypte, 1798-1801 (Paris, 1989)

- M. L .Pratt, Imperial eyes: Studies in travel writing and transculturation (London, 1992)

- P. Strathern, Napoleon in Egypt; the greatest glory (London, 2007)

- J. Urry and J. Larsen, The tourist gaze 3.0 (New York, 2011)

- S. Woolf, 'French civilization and ethnicity in the Napoleonic Empire' in Past and Present no. 124, (1989)

Citation

Robson, Fergus: French Soldiers encounter European and Arabic Architecture, (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---