Spoils of War in Egypt, 1798-1882

by Paul Fox

Reconquest of the Sudan Display Case (21st Lancers)

Image Credit: © The Queen's Royal Lancers and Nottinghamshire Yeomanry Museum, Nottinghamshire, England

Thirteen days after the 21st Lancers’ controversial charge at Omdurman on 2 September 1898, a soldier wrote to relatives in London from the banks of the Nile, north of Khartoum:

“My Dear Uncle and Aunt,

...No doubt you have read of the fight at Omdurman & and the great victory & have seen the account of our regiment's work & the charge. Tom and me went through it all & I am glad to say "Thank God" came out all right it has been an awful campaign for us [...] we are on our way down now to Cairo & it is awful nothing but hard biscuits and bully beef & marching in the sun all day & at night smothered with flies & insects.... I have seen enough of Egypt & the Soudan [...] I have got a spear & a couple of daggers which I will bring home with me all being well....

Your loving nephew, Herbert John Robinson.”

(Private Herbert John Robinson, 21st Lancers, 'Letter, Nile Expeditionary Force', National Army Museum, 1898)

Main Royal Masthead from French Flagship 'L'Orient' (c.1795)

Image Credit: © National Maritime Museum, London, England

Cap Badge, 44th (East Essex) Regiment (after 1874)

Image Credit: © NAM, London, England

Patrick Porter tells us that ‘armed conflict is an expression of identity as well as a means to an end’. From time to time between 1798 and 1898 soldiers and sailors like Herbert Robinson returned from Egypt with accounts of their experience, and with objects they had taken in combat, found on corpses, or purchased from Egyptians, Sudanese, or each other. Looting and trophy taking played an important part in defining personal and collective identities that were shaped by their cross-cultural experiences. The things people brought home influenced the way Egypt and the Egyptian Soudan were perceived and understood more widely in Britain, and how Britons at war constructed a sense of themselves.

Evidence of looting (private property taken from a combatant or a third party, dead or alive, in war), and trophy taking (anything serving as a token or evidence of victory, valour, or skill) on Egyptian territory can be found today in museums and archives all over Britain. This is hardly surprising: Raffi Gregorian has argued that ‘looting was endemic to most if not all armies of the nineteenth century’ (Gregorian, 'Unfit for Service, p. 84). Acquisitive acts, the taking of the spoils of war, were commonly regarded as an unexceptional aspect of armed conflict, even as late as 1898.

1798-1802

The material traces of conflict against revolutionary France in Egypt relate to a period when the promise of prize money was calculated to motivate sailors and soldiers. For example, six French ships of the line were captured by the British fleet led by Horatio Nelson at the Battle of the Nile in 1798. Their captors anticipated their legitimate share of the prize money (equivalent to over £11m today) as they escorted the seaworthy hulls to British naval bases.

Other trophies were purely symbolic. The lightening conductor at the masthead of the French flagship L’Orient, pulled from the sea after the ship exploded, was presented to Nelson. It is now a Nelson ‘relic’, but at the time it was a trophy whose meaning was grounded in the moral superiority of the Royal Navy, manifested at Aboukir Bay, and the promise of the defeat of revolutionary France.

On land, Alexandria and its hinterland had less to offer British troops in material terms, but it had classical ruins in abundance. Regiments with service in Egypt were subsequently granted permission to include a Sphinx motif over the word ‘Egypt’ in their cap badges, a form of indirect trophy taking that reflected the contemporary preoccupation with the ancient world, understood as the cradle of European civilisation.

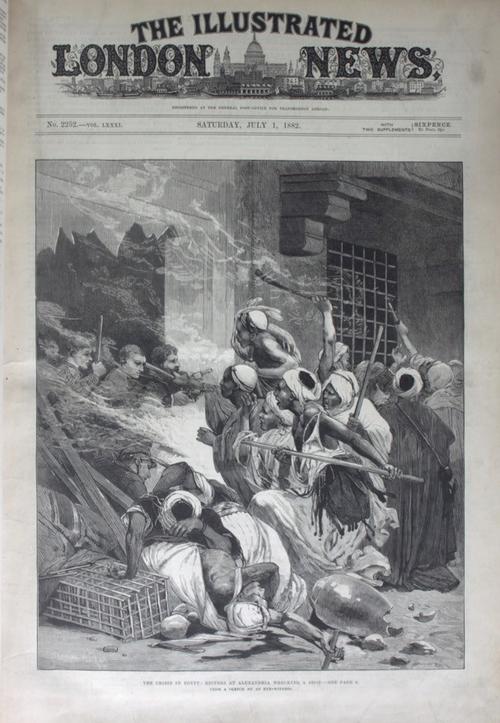

George Montbard, 'Crisis in Egypt: rioters at Alexandria wrecking a shop. From a sketch by an eye-witness, Illustrated London News (1 July 1882)

Image Credit: © Kensington and Chelsea Public Libraries, London, England

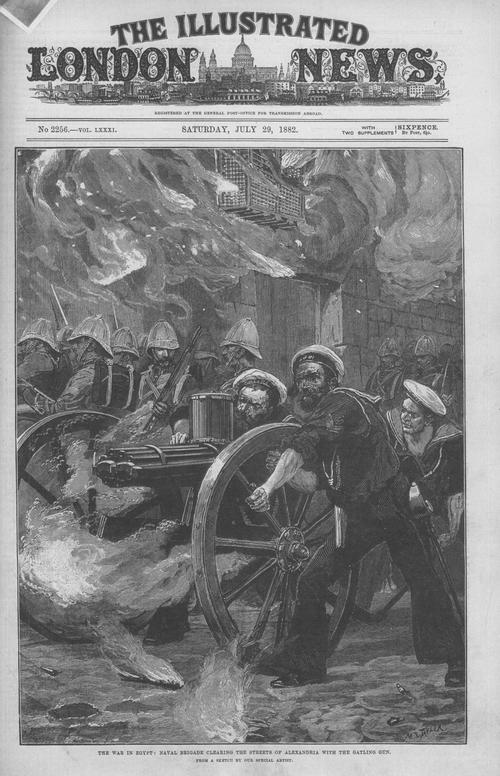

R Taylor, 'The War in Egypt: Naval Brigade clearing the streets of Alexandria with the Gatling Gun. From a sketch by our special artist', Illustrated London News ( 29 July 1882)

Image Credit: © Kensington and Chelsea Public Libraries, London, England

Attributed to Francis Gregson, 'Omdurman: Egyptian troops looting during interval between two fights (2 September 1898)

Image Credit: © NAM, London, England

1882

The ancient world in Egypt continued to fascinate Europeans for the rest of the century. Five years before the 1898 Omdurman battle Alfred Milner, until recently the Under-Secretary for Finance in Egypt, had criticised the way the Great Powers continuously appropriated Egypt’s material and cultural wealth. His 1893 England in Egypt, begins:

“More than two thousand years ago, the Father of History, in his comprehensive survey of the then known world, singled out Egypt as pre-eminently the land of wonders. ‘I speak at length about Egypt,’ he says, ‘because it contains more marvellous things then any other country, things too strange for words.’ […]

The fascination of its primeval monuments remains […] And as in its physical singularity, as in its stupendous antiquities, so in the life and habits of its people…Egypt is still, like the Egypt of Herodotus, the chosen home of what is strange and unexampled and paradoxical.”

(Milner, England in Egypt, 1893, pp. 1-2)

Milner argued that modern, reformed Egypt and its inhabitants should never again be regarded as a resource ripe for appropriation. Yet British servicemen did just that 1882, and continued to do so until the end of the century.

Attitudes to looting and trophy taking in 1882 were as complex as the socio-economic climate in which Britain found itself militarily engaged. In the face of a nationalist insurrection and a perceived threat to the Suez Canal, a British fleet first bombarded then captured Alexandria’s forts. Landing parties then pulled down Egyptian flags, which were taken as trophies. Less significant artefacts were looted by European sailors and soldiers on the ground. Yet the killings and arson that accompanied the subsequent looting of the resource-rich European quarter provoked an intervention during which the Royal Navy ignored Egyptian law, employing the machine gun and the firing squad to meet out summary justice to Egyptians caught in the act of looting.

The Egyptian army, armed with modern weapons, trained by American officers, and employing Western tactics, was subsequently defeated by the British expeditionary force at Tel-el-Kebir. The defeated force abandoned its tented camp, which became the first of many locations over the next two decades to be picked over by British soldiers and sailors of every rank, from General to private soldier: ‘officers as well as men were obsessed with grabbing all they could lay their hands on. Even the Duke of Connaught “acquired” some carpets and was seen…riding through the camp, “smoking a cigarette and with a silver coffeepot in his hand which he had just looted”. [Commanding General, Sir Garnet] Wolseley helped himself to a brace of Arabi’s pistols and a small copy of the Koran found in his tent’ (Wright, A Tidy Little War, 1882).

A longer paper on looting and trophy taking during the 1883—1898 counter-insurgency campaign also appears on the MWME website. This brief assessment of spoliation during the campaign in Egypt against Napoleon, and of the initial phase of Britain’s re-engagement with Egypt in 1882, has demonstrated how articulating notions of authority and ownership are fundamental to the determination of what Annette Weiner calls the '"dense" sociocultural meaning and value' assigned to objects that make up a society’s material culture (Annette Weiner, **, in Myers, 'The Empire of Things, p. 5). Specifically, what is at stake in wartime is the notion of authority assigned not to objects produced in a given society, but acquired by it during the cross-cultural encounters provoked by armed conflict.

Bibliography

- Raffi Gregorian, 'Unfit for Service: British Law and Looting in India in the Mid-Nineteenth Century', South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies, 13 (1990), 63-84.

- Alfred Milner, England in Egypt (London: Edward Arnold, 1893).

- Fred R. Myers, ed., The Empire of Things: Regimes of Value and Material Culture (Santa Fe, N.M.: School of American Research Press; James Currey, Oxford, 2001).

- Patrick Porter, Military Orientalism: Eastern War through Western Eyes (London: Hurst & company, 2009), pp. x, 263 p.

- Private Herbert John Robinson, 21st Lancers, 'Letter, Nile Expeditionary Force', (National Army Museum, 1898).

- William Wright, A Tidy Little War: The British Invasion of Egypt, 1882 (Stroud: Spellmount, 2009).

Citation

Fox, Paul: Spoils of War in Egypt, 1798-1882, (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---