Egypt on the Thames

by Paul Fox

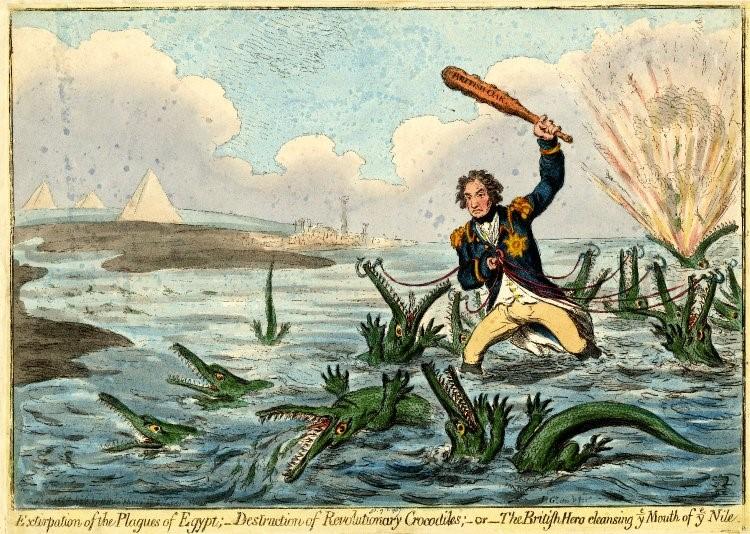

James Gillray, Extirpation of the Plagues of Egypt; Destruction of Revolutionary Crocodiles; or The British Hero Cleansing the Mouth of the Nile (1798)

Image Credit: © Trustees of the British Museum, London, England

Hunters for gold or pursuers of fame, they all had gone out on that stream, bearing the sword, and often the torch, messengers of the might within the land, bearers of a spark from the sacred fire.

Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness

Sir Reginald Blomfield (pylon) and William Reid Dick (sculpture), Royal Air Force Memorial, Whitehall Extension, Victoria Embankment Gardens (1923)

Image Credit: photograph:Paul Fox

Sir Hamo Thornycroft, General Charles Gordon Memorial, Victoria Embankment Gardens, Whitehall Extension (1887)

Image Credit: Photograph: Hāleh Anvari

Drum, captured by Dervish forces from Hick's 1883 expedition, recovered during Dongola expedition (1896)

Image Credit: © NAM, London, England

Joseph Whitehead (drinking fountain) and Sir Joseph Edgar Boehm (medallion), Herbert Stewart Memorial, Hans Place, London (1887)

Image Credit: Photograph: Paul Fox

J.T. Tussaud, the Mahdi Group (after 1885)

Image Credit: © Madame Tussaud's

Obelisk of Tuthmosis III ('Cleopatra's Needle'), Victoria Embankment, originally at Heliopolis, Egypt (c.1450 BCE)

Image Credit: Photograph: Hāleh Anvari

George John Vulliamy, Sphinx, Victoria Embankment (1878)

Image Credit: Photograph: Hāleh Anvari

Benches with Sphinx Motifs, Victoria Embankment

Image Credit: Photograph: Hāleh Anvari

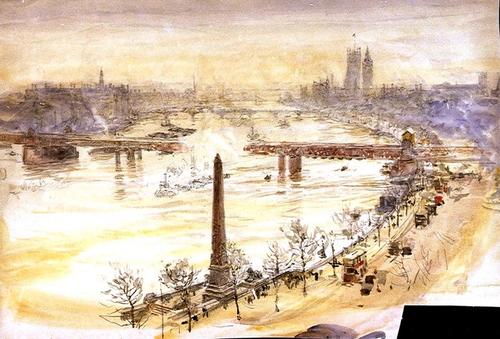

William Wyllie, Charging Cross Bridge (after 1878)

Image Credit: © National Maritime Museum, London, England

Main Royal Masthead from French Flagship 'L'Orient' (c.1795)

Image Credit: © National Maritime Museum, London, England

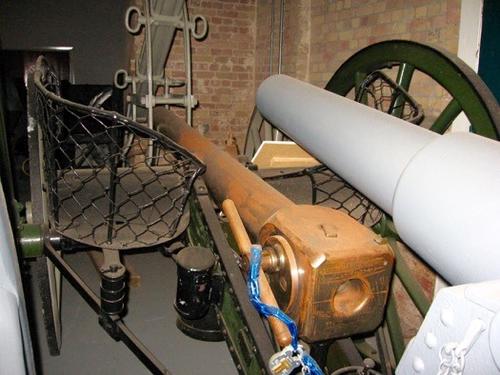

2.5 Inch RML Mountain Gun (c.1880)

Image Credit: Firepower, Royal Artillery Museum, London, England; Photograph: Paul Fox

Krupp C73 Field Gun, Captured at Tel-el-Kebir (1882)

Image Credit: Royal Artillery Museum, London, England; Photograph: Paul Fox

Reconquest of the Sudan Display Case

Image Credit: The Royal Engineers Museum, Gillingham, England; Photograph: Paul Fox

Onslow Ford, Gordon Memorial (1890)

Image Credit: Brompton Barracks, Chatham, England; Photograph: Paul Fox

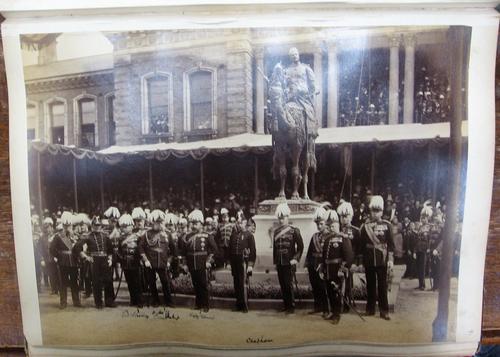

Album photograph, Unveiling Ceremony, Gordon Memorial (1890)

Image Credit: Royal Engineers Museum, Gillingham, England; Photograph: Paul Fox

Did you go to the exhibition Bonaparte and the British: Prints and Propaganda in the Age of Napoleon at the British Museum (until 16 August 2015)? If you did, you probably looked at this engraving by prominent satirist, James Gillray. Published in December, four months after the Battle of The Nile (1—3 August 1798), it depicts Horatio Nelson, who led the British fleet to victory, standing colossus-like in the estuary of the Nile with the Giza pyramids and city of Alexandria behind him. The battle is refought in the print: The British warships (Nelson) break into the French fleet (crocodiles) in an aggressive manoeuvre that shatters French cohesion. One crocodile (the frigate Sérieuse) sinks, other ships flee, many are taken as prizes, while the French flagship, Orient, explodes.

Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt triggered a military response putting British ‘boots on the ground’ during the first of many operations over the next century. A British expeditionary force finally expelled the French army from Egypt in 1802, but five years later the British Army briefly occupied Alexandria. In 1882 Britain intervened to crush a military coup in the Nile delta. Soon afterwards British forces were committed to countering a long-running Islamist insurgency that lasted until 1899. During the First World War large numbers of British and Empire troops trained in, and operated out of, Egyptian territory.

The material traces of those wars are scattered all over Britain today. Gillray took us all the way to the Nile to celebrate a major naval victory, so let’s follow his example and head down to the river: the River Thames. There, on the Victoria Embankment and beyond, we can plot out how British wars in Egypt are remembered today.

Our journey begins in the riverside grounds outside the Ministry of Defence in Whitehall, where a large gilded eagle perches on a stone pylon between the trees on the Embankment, looking out across the Thames. This monument to the dawn of airpower commemorates the Royal Naval Air Service, the Royal Flying Corps, and, from April 1918, the Royal Air Force. It is, in part, a memorial to all those who participated in operations in Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean during the First World War.

Walk 100 metres or so to the junction with Horse Guards Avenue to find Hamo Thornycroft’s Gordon Memorial by the entrance to the Whitehall Extension. Gordon’s death in Khartoum in January 1885 sparked an outpouring of grief in Britain where he was lionised for his principled stance against slavery, and for his refusal to abandon Egyptian troops under his command to the forces of an Islamic insurgency. Thornycroft’s statue stood in Trafalgar Square until 1943, when it was removed to make way for wartime propaganda installations. It wasn’t until 1953 that it was re-erected in its current, less prestigious, location.

Leave the Whitehall Extension, and walk downstream to the section of Victoria Embankment Gardens just past Embankment Underground Station. Here you will find Cecil Brown’s modest memorial to the members of the Imperial Camel Corps who served in Egypt, Sinai and Palestine during the First World War. You probably thought you had finished with Gordon when you left him gazing down the Nile from the roof of the Governor’s Palace in Khartoum; but did you know that the Camel Corps was raised in 1884 to provide mounted infantry to spearhead the (unsuccessful) Nile Expedition to rescue him from Khartoum?

Gordon is very present in London. If you have time later catch the Tube to Knightsbridge to find the related memorial to General Herbert Stewart in Hans Place, behind the Harrods department store. In 1884 Stewart was a rising star in the British Army. He had led the cavalry pursuit into Cairo in the closing phase of the 1882 Egypt campaign, and then secured his reputation as a battlefield commander during fighting around Suakin in early 1884. Later that year he led the Desert Column (Camel Corps and cavalry) in a desperate bid to cross the neck of the Great Bend in the Nile and reach Khartoum before it fell. The attempt failed and Stewart was mortally wounded during one of the most close-fought battles of the era.

Did you know that Gordon’s ‘portrait’, or wax work, was a popular exhibit at Madame Tussaud’s for over 40 years? Madame Tussaud’s business model (and she was a formidable business woman) included collecting as many ‘authentic’ ‘relics’ to clothe, equip and accompany the wax figures as the company could get its hands on. Unfortunately, the building you visit today was gutted by fire in 1925. Almost everything on display was destroyed, including Gordon’s very own camel harness; but photographs of earlier exhibition displays have survived. In this one we see four Egyptian Sudan ‘portraits’ grouped together. From the left: General William Hicks, General Charles Gordon, Muhammad Ahmed (the self-proclaimed Mahdi), and Gordon’s aide, Colonel John Stewart. All three British officers were killed by Ahmed’s jihadist forces on different occasions between September 1883 and January 1885. The ‘Mahdi’ himself died of typhus six months later. At the base of this popular shine to British martyrs, visitors were able to gaze at ‘relics’ associated with their lives and the military campaign in the Egyptian Sudan, including swords, helmets and items of equipment.

Returning to the Embankment, however, turn away from the Camel Corps Memorial and take the path through the nearby café that leads onto the Embankment itself. Look across the road and slightly to your left to locate ‘Cleopatra’s Needle’ and its associated bronze sphinxes, an object associated with the British campaign against Napoleon in Egypt and the Mediterranean. The British army had tried to transport it to Britain in 1802 and even constructed a specially-designed wharf, but it proved too difficult to move. In 1877 it was lifted into a specially designed floating iron cylinder to be towed to Britain. The cylinder had to be cut adrift during a storm in the Bay of Biscay. Luckily, fishermen found it four days later, and the obelisk finally made it up the Thames on 21 January 1878.

The principal inscription on its new base reads:

This obelisk

Prostrate for centuries

On the sands of Alexandria

Was presented to the British nation A.D. 1819 by

Mahommed Ali Viceroy of Egypt

A worthy memorial of our distinguished countrymen

Nelson and Abercromby

Two bronze sphinxes flank the Needle and Egyptian motifs feature on the Embankment’s street furniture. Note how the upstream Sphinx was damaged by shrapnel during the first aircraft bombing raid on London on the evening of 4 September 1917.

British entanglement with Egypt’s ancient and modern histories is especially present at this site, which today is hidden by the canopies of neighbouring trees, and more recent monuments compete for attention along this stretch of the river. It wasn’t always like that; William Wyllie represents the Needle as dominating the sweep of the Victoria Embankment shortly after being installed.

Walk back up the Embankment and take a river boat from the pier just below Charing Cross Bridge (you can see it Wyllie’s work) to Greenwich, and follow the signs to the National Maritime Museum. Make your way to the top floor exhibition, ‘Nelson, Navy, Nation’. Here you will discover just how significant the Battle of the Nile was at the time, and still is to our popular understanding of the Napoleonic wars.

The masthead of the Orient was pulled from the sea after the ship exploded during the Battle of the Nile. It was acquired by Nelson, who placed it on display in his house at Merton. Today it is valued as a significant relic associated with the life of Nelson in an exhibition in what is, in effect, a shrine (yes, another one) to Nelson in a national museum.

If you want to see examples of military equipment used by the British armed forces, or taken as trophies, during wars in Egypt, take the Tube or river ferry to Woolwich Arsenal and follow the signs to Firepower, The Royal Artillery Museum, on the south bank of the Thames. The label accompanying the 2.5 Inch RML Mountain Gun on public display informs the visitor that this type of weapon ‘was widely used, especially in the campaigns in the [Egyptian] Sudan between 1883—84’.

Unfortunately, the object of greatest interest to us is a German-made Krupp C73 Field Gun currently in storage. In 1882 a joint Royal Navy and Army expeditionary force checked the ambitions of Egyptian nationalist Ahmed Urabi, restored the established political order, and secured British interests in the region. The short campaign culminated in British victory at Tel-el-Kebir, after which several captured Krupp guns were shipped to Britain. Like Gordon’s statue originally sited in Trafalgar Square, and the obelisk obscured by foliage on the Embankment, the C73 has been relegated to the margins of the museum – and our historical consciousness.

If you are motivated to follow the trail still further down the Thames, take a train to Chatham and visit the museum of the Corps of Royal Engineers, which also contains material removed to Britain after Egyptian campaigns. As befitting an organisation whose role includes construction as well as destruction, the display case representing the 1898 Nile expedition to recapture the Egyptian Sudan includes a salvaged tile from the roof of Gordon’s residency (No. 12 on the above photograph) next to a section of the top rail removed from the Mahdi’s tomb in Khartoum shortly after the battle of Omdurman (No. 8).

Complete your tour by exiting the museum to find Onslow Ford’s memorial to Gordon, unveiled by the Prince of Wales on 19 May 1890 in the presence of Field Martial Sir Garnet Wolseley and many others who had taken part in operations in Egypt and Sudan over the previous 50 years.

This walk, which has traced the British memory of campaigns in Egypt, begins and ends with statues of Gordon. After his death Gordon was represented as an exemplary character: a successful imperial warrior and a Christian martyr who had placed principle before political expediency. He became, as we might say today, a ‘national treasure’. But after the First World War, Gordon and the ‘small wars’ of empire began to recede into the distance. The marginal status accorded many of the memorials we have encountered on this walk suggests how the dominant political and social memory of the two World Wars has eclipsed that of earlier conflicts, including the Napoleonic wars, and those of Britain’s imperial era. The campaigns in Egypt may not resonate strongly in British culture today, but the material traces of what were once deemed significant historical events are nevertheless woven into the fabric of metropolitan memorialisation. They remind us of what we chose to remember and what we elect (almost) to forget.

Citation

Fox, Paul: Egypt on the Thames (2015), URL: http://www.mwme.eu/essays/index.html

---

---